Siyang Xu writes a detailed tactical analysis about the Premier League match that ended Chelsea 4-0 Manchester United.

Mourinho and his Manchester United side came to Stamford Bridgethis past weekend for their second tough away Premier League game of the week. It should suffice to say that Mourinho’s return did not go as planned, with Chelsea routing his team 4-0. The result sent shockwaves through the football world, with the skeletons still tumbling out of that particular closet.

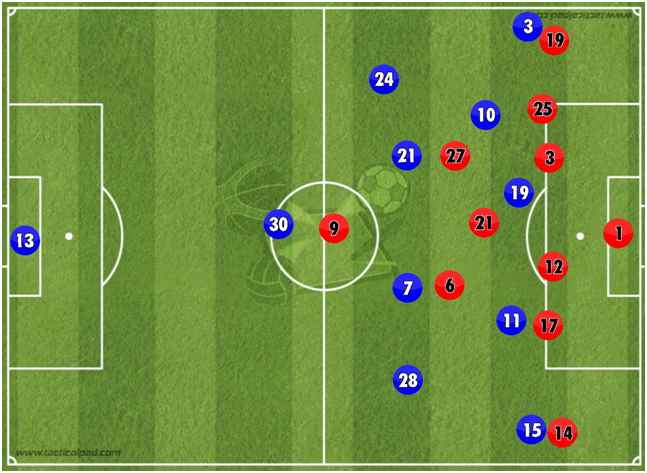

made using TacticalPad

Chelsea: 13. Courtois; 28. Azpilicueta, 30. David Luiz, 24. Cahill; 15. Moses, 7. Kante, 21. Matic, 3. Marcos Alonso; 17. Pedro, 10. Hazard, 19. D. Costa

Manchester United: 1. De Gea; 25. Valencia, 3. Bailly, 12. Smalling, 17. Blind; 21. Herrera, 6. Pogba, 27. Fellaini; 19. Rashford, 14. Lindgard, 9. Ibrahimovic

Three at the back

Antonio Conté’s 3-4-3 system offered Chelsea several strategic advantages against Manchester United. Primarily, the presence of the extra defender created an overload which allowed for greater ease of circulation, especially horizontally, in build up.

Man Utd adopted a similar man-orientated approach as their strategy last Monday against Liverpool, but with a slight difference. Instead of playing a 2-1 in central midfield, United had a 1-2 with Ander Herrera sitting behind Marouane Fellaini and Paul Pogba. This is likely to be because Mourinho did not see the point of having one of his midfielders join Zlatan Ibrahimovic on the furthest line of defence, as Chelsea’s three centre backs would have a numerical advantage against United’s front line regardless of whether it contained one or two players.

This is a common approach for managers facing a team which plays three at the back – instead of wasting a player further up the pitch in an area the opposition will naturally control anyway, the player would be dropped back to provide solidity deeper down the pitch. This means that the opposition will have a 3vs1 overload on the first line of their build up – one usually considered meaningless by the defensive manager due to its harmless deep position on the pitch.

Chelsea, however, were able to put this 3vs1 overload to good use due to the outer centre backs’ confidence in stepping out of the defensive line and affecting play further up the pitch. Man Utd’s man-marking strategy was pretty obvious – the two central midfielders, Fellaini and Pogba, would pick up Chelsea’s two central midfielders, whilst the wingers would stay tight to their respective wing backs. However, it was not clear how Mourinho wanted to deal with Chelsea’s centre backs stepping into midfield.

With the two central midfielders, Nemanja Matic and N’golo Kanté, being marked closely, they were never able to turn when receiving the ball whilst facing their own goal. However, with Azpilicueta and Cahill offering themselves as an option either side, Chelsea kept being able to find a free man to help advance the ball. When Azpilicueta or Cahill were on the ball, Pogba and Fellaini were never sure whether to close them down, leaving their designated marker free, or to stay with their man in central midfield, offering the centre back the opportunity to carry the ball forward. These 2vs1 situations in each half space enabled Chelsea to comfortably keep control of possession whilst looking to move the ball forwards.

When Pogba or Fellaini did go out to press the centre back, Ander Herrera often had to step out of his deeper position protecting the back four to pick up the central midfielder that had been left free. In theory, this is not a disaster for Man Utd, but Chelsea’s front three showed good intelligence with their movement and whenever this happened, managed to find positions which opened up passing lanes through Man Utd’s midfield line. Chelsea’s passing was crisp and sharp, enabling the player to release the ball before Man Utd’s tight marker was able to get a foot in.

If a forward passing opportunity didn’t arise, Chelsea’s structure gave them good positional coverage across the width of the pitch, allowing for easy horizontal circulation. This forced the Man Utd block to repeatedly shift from side to side. When this happens, the chances of a gap appearing within the block becomes very high, as it is very difficult to co-ordinate and keep distances between players for a prolonged period of time. Once again, with the presence of the outer centre backs in midfield areas, Chelsea’s central midfielders always had an extra passing option to continue circulating the ball. When Chelsea successfully drew Man Utd towards one side of the pitch, they were able to quick re-circulate the ball the other way, where there would be space for the far centre back to advance with the ball (shown below). At the same time, the far wing back would pull as wide as possible to ensure that Man Utd’s winger goes with him, creating more space centrally.

The advantages of advanced wing backs

The positioning of the wing backs was also key to Chelsea’s success further up the pitch. During the Liverpool game, it was clear that Mourinho had instructed his wingers to follow Liverpool’s full backs as far back as needed, often dropping back into the defensive line. This meant that United spent large periods of that game in a 6-3-1 block.

Conté clearly recognised this as a potential situation in which Chelsea could thrive. He instructed his wing backs to push United’s wingers as far back as possible, once again forcing United into a 6-3-1 shape. Not only did this neutralise United’s main counter attacking threats by forcing them into such a deep position, but also severely reduced United’s coverage in midfield. As seen by the diagram below, United were left with just three players to cover such a large area in front of their defence. Chelsea were able to use intelligent movements and combinations to pull them apart and find space to create dangerous attacks.

United’s full backs didn’t seem to fully understand their role against their opposing wing back, often creating confusion in defensive situations. This was most clearly highlighted in the third Chelsea goal, where Valencia, instead of tracking Hazard’s run in behind United’s defence, moved towards the wing to mark Marcos Alonso. In hindsight, and through the lens of the spectator, it was a crazy decision, with Hazard clearly being the most dangerous threat in a central area.

However, Valencia was clearly not used to having different reference points when defending against a team that uses wing backs. Defenders in each position usually have specific reference points to determine their actions in different situations. For a right back, for example, a winger running in the channel would be an obvious reference point for him to track the run. In this situation, however, the presence of Marcos Alonso out wide as a wing back complicated Valencia’s thinking. Having just seen Mata track Hazard as he moved inside, he assumed that Mata would follow his run even as he looked to penetrate the United defensive line.

Had Hazard been playing as an orthodox winger, and Alonso as an orthodox full back, there is no doubt that Valencia would’ve known that Hazard would’ve been his responsibility to mark once he began to make a move behind, leaving Alonso for his winger (Mata) to deal with. However, the different responsibilities he was given against a team playing 3-4-3 was evidently still novel to Valencia and a lapse of judgement, made under pressure, saw the game well and truly ended with Chelsea going 3-0 up. With many teams playing 4-2-3-1 in the Premier League for a number of years, most defenders have not faced the range of tactical systems they would’ve done if playing abroad, and it could be some time before players adjust accordingly to the relatively uncommon (in England) 3-4-3 system Conté is using.

Even though the two first half goals came via two defensive individual errors (although the general collective could be blamed for poorly defending the corner for Cahill’s goal), Chelsea managed to control the game effectively with this structure in attack. They managed to successfully contain Manchester United’s counter attacks, with Ibrahimovic often coming deep to collect the ball in a bid to start attacks but failing to progress anywhere due to a lack of supporting runners around him (largely down to how deep the wingers were, as referred to earlier).

Half time switch

At half time, Mourinho switched to a 4-4-2 in a bid to get back into the game. This did indeed put Manchester United into more attacking positions, but due to the extremely un-compact shape, United were often left very exposed on the counter attack. With huge spaces between the lines, Chelsea were regularly able to play through United with ease, duly finishing the game off on the counter with even the most limited attackers finding space to attack United’s defence, as exemplified by Kante getting on the scoresheet.

Defensively, Chelsea were very happy to adjust and settle into a very deep 5-4-1 block (often as far as their own 18-yard line) from the beginning of the second half, safe in the knowledge of their two goal lead. The two defensive lines were very compact, preventing United from playing through in central areas, whilst Costa stayed forward to offer an outlet on the counter.

Manchester United stuck to their strategy of attempting to use their height advantage with persistent crosses into the box. Over the course of the game, some decent openings fell to the likes of Ibrahimovic and Rashford, but clear chances were not regular enough for United to have had any real confidence in getting past Courtois, who also happened to have a very good game. Ibrahimovic was able to isolate Azpilicueta at the back post a couple of times in the first half, missing a gilt-edged opportunity to score, but Chelsea adjusted in the second half by making their block narrower when defending crosses, reducing the space that Ibrahimovic had to attack.

United’s best chances came through isolation scenarios in wide areas, especially when Valencia was able to run at Alonso in a 1vs1, before getting to the byline and crossing. However, these situations were largely quite rare, with Chelsea usually able to provide defensive cover within their compact block from other players for their wing back.

Conclusion

Conceding a goal after 30 seconds is never ideal, but to give away a second in the first half from a set-piece was suicidal and effectively ended United’s hopes of getting back into the game. It’s difficult to react when your game plan is primarily focused on defence and an opposition goal in the first minute forces you to alter your priorities, but United and Mourinho need to show better adaptability within matches if they are to get themselves back into the title race. It’s no secret that Manchester United have struggled to come back from conceding the first goal in matches this season, which largely stems from the fact that Mourinho’s side lack a clear attacking strategy beyond assaulting the opposition box with crosses.

Read all our tactical analyses here.

- Liverpool 3-2 PSG: Liverpool edge deserved victory against dysfunctional PSG - September 21, 2018

- Tactical Analysis: France 1-0 Belgium | Set Piece Decides Game Dominated by Determined Defences - July 14, 2018

- Tactical Analysis: Manchester City 4-1 Tottenham Hotspur | Guardiola extends winning run to 16 - December 20, 2017