Greg Lea takes an in-depth look at catenaccio, the 3-5-2 and what Italy’s obsession with tactics and strategy tell us about the country’s history and culture.

“In twenty minutes here”, Rafael Benitez exclaimed at his first Napoli press conference in 2013, “I have been asked more tactical questions than in an entire year in England”.

Italy has always been that way. Whereas in England the mainstream media talk more of psychology and man-management, Italians love to dissect strategies and theories, fans and journalists forcing coaches to explain their plans in the most intricate detail.

In December last year, Benitez himself fielded in-depth questions from reporters about his 4-2-3-1 system after his team had fallen eight points behind leaders Juventus: according to the members of the press present, Napoli’s shortcomings could be addressed by flipping the formation to 4-3-2-1, which would provide better midfield cover and allow the side’s attacking full-backs to push on without exposing the Partenopei defensively.

It would be rare to witness such technical discussions in an English press room. During his time at Liverpool, Benitez tended to be primarily judged as aloof and a poor motivator, and any talk of his tactics was usually tinged with a sense of regret that he was unwilling to let off the shackles and “go for it” a bit more. Analyses of second-half comebacks in the Premier League usually focus on the presumed tub-thumping speech given by the manager at half-time, while similarly turnarounds in Serie A are attributed to the tactical tweaks made by the man in charge at the interval. An open 4-4 draw is seen by the English as wonderfully entertaining; in Italy, where iconic football writer Gianni Brera once declared that the perfect game would finish 0-0, they ask what went wrong.

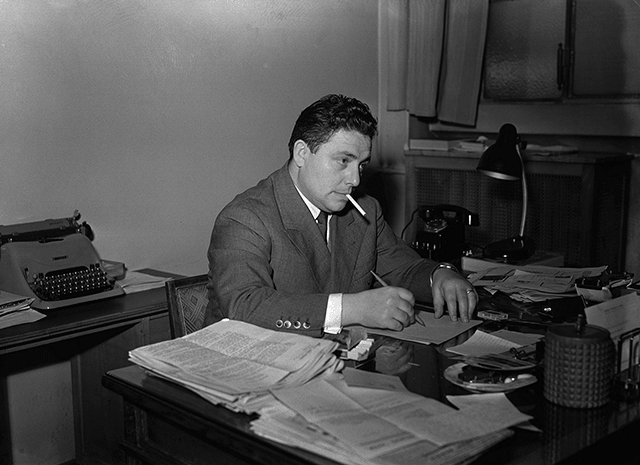

Gianni Brera | Image

As with most things in football, there is no right or wrong in all this. In the same way that nations have distinct cuisines, customs and ways of life, the game is played and watched differently across the world, divergent emphases and perspectives fueling different views and opinions. The assimilating effects of globalization may have diluted these distinct cultures, but historical elements of a nation’s footballing psyche remain today. Indeed, far from being a recent development, Italy’s infatuation with theory has deep roots.

Brera was no ordinary journalist. An exceptional writer credited with the invention of hundreds of new football-related words, his talents propelled him to an unprecedented position of authority within the game. At 30, he became the youngest ever editor of the prestigious La Gazzetta Dello Sport – one of three national sport dailies dedicated predominantly to football, a sign of Italy’s thirst for things to read about the game – and, as time went on, it would be rare for a week to go by without his work being featured at least once in each of Italy’s major publications. This level of power was unique, and Brera was not shy in using it to expound his theories on how calcio should be played.

Likely influenced by Italy’s crushing failure at World War Two, Brera saw Italians as physically weaker than their international rivals, so advocated a focus on strategy and gamesmanship to overcome these supposedly intrinsic ethno-cultural limitations. Appearing on television as well as in the written press, Brera spread his ideals of the counter-attack and defensive solidity to a country humbled by the devastating military defeat of 1945, arguing that Italy must focus on out thinking the opposition since they would not be able to overcome them with strength or skill.

Such a negative outlook was not altogether out of place in Italy, whose history of invasion and occupation by various greater powers – as well as the vulnerability induced by its peninsular state – have contributed to what Gianluca Vialli and Gabriele Marcotti term a “congenital insecurity complex” in their excellent book, The Italian Job. Together with the ruinous state that many Italian cities found themselves in after the heavy bombing of the war, this bred a culture of pragmatism: as Mario Sconcerti, the Corriere della Sera journalist, explains, “it was impossible to think big [given the state of the country]”. This was true in all aspects of Italian life, and football was no exception.

The tangible result of this mindset was catenaccio, the most infamous tactical arrangement in history. Its roots lay in Switzerland with Karl Rappan, the Austrian coach, but the system is most synonymous with Helenio Herrera’s Inter side of the 1960s, who won three scudetti and two European Cups using it.

Threatened with the loss of his job after finishing third and second in his first two campaigns, Herrera decided to go back to basics, removing a midfielder from Inter’s line-up and re-positioning him behind the defence. Armando Picchi, the man who filled that role, became known as a libero: the defenders in front of him would man-mark the opposition’s attackers, leaving Picchi free to sweep up behind them.

![Helenio Herrera [centre] | Image](https://outsideoftheboot.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Helenio-Herrera-Inter-e1427225112791.jpg)

Helenio Herrera | Image

The Argentine protested that his system was not necessarily defensive, attesting that it is only remembered as such because of other clubs’ poor imitations. This is arguable, but what can be said with certainty is that catenaccio reflected the paranoia and insecurity present in Italy’s post-war national character.

The setup was all about minimising risks through a safety-first approach: Inter’s libero did not carry the ball forward à la Franz Beckenbeaur but instead acted as merely a second line of defence, while it was not uncommon to see all eleven Nerazzuri packed behind the ball when out of possession. This produced some joyless but undeniably effective football, which perhaps explains why Brera was such a fan, regularly filling his columns with praise for Inter and their manager’s methods. As the filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini crucially asserted, though: “Catenaccio was not invented by Gianni Brera, in the same way as the slums around Rome were not invented by those in neo-realist movies. It was part of the Italian character…it could not be invented”.

Catenaccio soon developed into Zona Mista, a variation which involved a more progressive role for the libero but which still retained many elements of Herrara’s configuration: Italy, for example, won the 1982 World Cup with Gaetano Scirea as sweeper, Bruno Conti as a “returner” at right midfield and Antonio Cobrini as an attacking left back. Inter’s domestic and continental success and Italy’s global triumph perpetuated the reactive mentality and instigated a process whereby a style that reflected this outlook permeated through Italian football so comprehensively that it became entrenched.

Zona Mista was labelled “The Italian Game” and young players were developed within this prevailing framework, which perhaps explains the historical dearth of talented Italian wingers: there has never been a tradition for a touchline-hugging winger in Italy, with wide players expected to tuck inside to stay compact and contribute to the side’s defensive efforts by consistently tracking back. Since tactics were relied upon to win games, individual talent had to be marginalised for the greater good of collective strategy.

Catenaccio as a specific tactical system, with strict man-making and a sweeper stationed permanently deeper than the rest of the defence, is now dead. The Italian state of mind that enabled it, however, lives on, its modern manifestation the 3-5-2 formation that has always been popular on the peninsula.

Antonio Conte | Image

It is important to stress that there is nothing inherently defensive about three-at-the-back; formations, after all, are neutral, and it is their application that defines the overall approach. Indeed, two sides can employ the same formation in very different ways: Antonio Conte’s Juventus pressed high and dominated possession when using a 3-5-2, while Walter Mazzarri’s Inter preferred to sit deep before getting the ball forward quickly in transition.

Nevertheless, the 3-5-2 invariably satisfies the Italian desire for security that catenaccio also aimed to assuage. Against a 4-4-2, it offers a spare man in both defence and midfield, the former providing cover as the other two defenders pick up the opposition striker, the latter boosting a team’s chances of controlling the ball. This extra midfielder is lost against a 4-3-3 or 4-2-3-1, but since the 3-5-2 then benefits from a 3 v 1 at the back, one of the centre backs can step forward into midfield when in possession, a role expertly performed by Leonardo Bonucci at Juventus.

No system is perfect, and teams lining up in a 3-5-2 often leave themselves vulnerable in the channels, particularly on the counter when teams can attack the space vacated by a wing-back. However, most sides are content to concede space in wide areas if it means they compress the centre: Atletico Madrid provided a masterclass of this approach in their matches with Barcelona last season, ceding the wide areas to remain narrow and compact in the confidence that they would be comfortable dealing with any crosses that the Catalans put in. As Jonathan Wilson, the tactics writer, explains: “[3-5-2] is a way of getting width high up the pitch without sacrificing men in the middle…Italians are obsessed by getting men in the middle and closing the game down, which is why [their] game is much more based on tactics and strategy than ours”.

3-5-2 is by no means the modern incarnation of catenaccio, and the defeatist attitude exhorted by Brera that Italians must win by strategy as they cannot do so with superior ability has thankfully been discarded. However, Italy is still intrigued by the theoretical and the strategic, and Serie A continues to be known around the world as “the tactical league”. This mentality, existing as it has done for over half a century, must speak to something deep within what it means to be Italian; according to La Gazzetta’s Fabio Lacari, “football theory is part of our culture”.

It would seem, too, that the security provided by the 3-5-2 and its potential for spare men, compactness and defensive solidity strikes a certain chord with Italians: Italy’s highest-profile modern-day managers – Fabio Capello, Carlo Ancelotti, Marcello Lippi, Antonio Conte – have all used it at some point throughout their careers. The formation has been employed elsewhere on the continent this season, most notably by Manchester United in England and Barcelona in Spain, as well as Mexico, Costa Rica and Holland at the 2014 World Cup, but 3-5-2 remains associated with the Italian game.

Whether these traditions continue indefinitely in an ever-globalised world remains to be seen. Brazil and Germany demonstrated how outdated some national stereotypes can be at football’s showpiece event last summer, and globalisation and mass immigration have seen distinct styles become increasingly overlapping and intertwined.

Historical elements remain to some extent, though, and Rafa Benitez and his Serie A counterparts should remain aware that, if they are considering a midfield diamond at the weekend, they better be prepared to explain their rationale to interrogative Italian journalists afterwards.

Written by Greg Lea

- From the Catenaccio to the 3-5-2: Italy’s love affair with tactics and strategy - March 25, 2015

- Euro 2012: Croatia 0-1 Spain | Epitome ofthe Control of the Game - February 11, 2015

- Catenaccio: Inter’s Tactical Set-Up Under Helenio Herrera - October 20, 2014