While Asian football is steadily rising in the World, it is strange that the two most populous countries are still a long way away from the top. Often dubbed “sleeping giants”, China and India are making strides to cut the gap though. The former, especially with a football loving President in Xi Jinping, are looking the part with massive changes in recent times.

While the modern game of football was cultivated in Britain, the origins of the sport can be traced all the way back to ancient China, and a game known as cuju. Cuju can be roughly translated as “kick ball” and was played with a leather ball stuffed with feathers, which was kicked between two poles to score a goal. Although far more basic, it shares the fundamental motions of the beautiful game we know today.

Military leaders encouraged their soldiers to play the game as it improved the men’s fitness and promoted healthy competition. It’s inclusion in Chinese military handbooks is the reason we are aware of its origins today.

Despite this early form of football being so widespread in Chinese culture – the game was later extended to female and civilian teams and was played in royal courts and amongst the upper classes – the sport died out in the 17th century. The concept of football largely faded from China until it was reintroduced in the early 1900’s where it grew to be one of the most followed sports in the country, after the countries favourite: basketball.

Despite the popularity of football and the country’s huge population, the Chinese national team has never been a major player at international tournaments. In 2002, they qualified for the World Cup thanks to the Serbian coach Bora Milutinović. Despite losing all three group matches and failing to score a goal, it was seen as a huge achievement for the team. China have fared better in the Asian Cup, finishing runners up in 2004, 1984 and most recently as quarter finalists in the 2015 competition.

Chinese domestic football was re-branded and re-launched in 2004 as the Chinese Super League, replacing the old Chinese Jia-A League. The Jia-A league grew out of the post-war football culture that existed in China, a mass of local sporting clubs, institutes and army sports units. These various clubs would participate in regional tournaments but were prevented from playing in the various national leagues, which were reserved for official clubs only.

Through a steady process of sponsorship and ownership along with the formation of structured leagues, Chinese football grew into the European model of a single, national league system with many tiers for amateurs to the country’s best sides.

The Super League was the Chinese Football Association’s attempt to improve the standard of football in the country. A set of strict criteria was drawn up for teams competing in the league, which covered aspects such as financial management, a progressive youth development system and also encouraged clubs to attract high profile foreign managers and players.

Despite this, European interest in the Chinese game remains marginal, and many bookmakers like Ladbrokes fail to offer any markets.

The football association realised that big international names would increase interest amongst fans and attract youngsters to the sport, increasing the pool of players clubs had to recruit from, along with providing a better spectacle for fans.

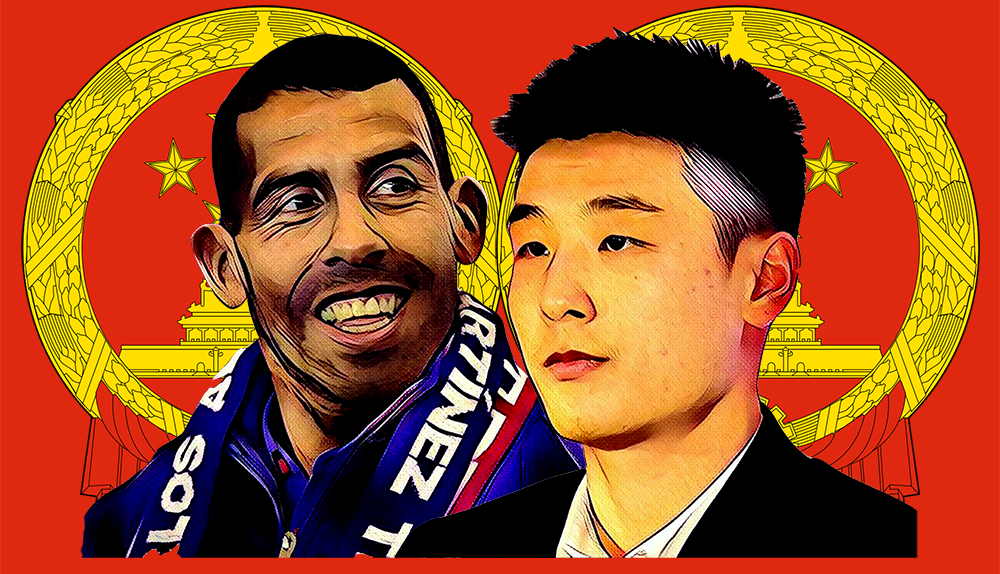

Since the Super League was founded, players such as Nicolas Anelka, Alberto Gilardino, Paulinho, Robinho and Vágner Love have all featured for a variety of top clubs. China is known as a common destination for Brazilian players who are entering the latter stages of their careers.

Brazil legend Ronaldo recently announced he intends to open 30 football schools in China. Since his retirement in 2011, Ronaldo has become an ambassador for the game and states that his aim is to assist the country in refining their training methods and instilling European-style football philosophies into the game.

It is no coincidence that Ronaldo chose China: the country has made a football revolution one of its top priorities, largely because President Xi Jinping is a huge football fan. Before he took China’s most powerful position, he outlined three personal ambitions for the country, all three were football-related.

The feared football lover has instigated a football renaissance across the country, as officials hurry to please their leader. Football has become a compulsory part of the national curriculum and, by 2017, the country expects to have opened no less than 20,000 football themed schools, although nobody has specified quite what is making way on the syllabus.

China has also sought to create footballing ties with some of Europe’s biggest nations. In 2015, they signed a memorandum of understanding (a kind of “gentleman’s agreement”) with the United Kingdom to help develop football in China. This includes the formation of academies and exchange programmes for young players. The deal was likely as not brokered by the two nation’s strong economic ties.

There are also talks of similar networks being established with French and Dutch authorities as China hopes to bring the European philosophy back home; though one has to wonder why they have not pursued more German connections, as the model they created just over a decade ago yielded one of the greatest generations of footballers in history.

That being said, one of the flagships of the football revolution, the Evergrande International Football School in Qingyuan, boasts many coaches plucked from La Liga, and many have ties to the Madrid clubs.

With over 150 coaches, 50 football pitches, Olympic-sized swimming pools and more, the Evergrande complex dwarfs similar European setups and is the largest football school in the world. It also demonstrates that China has identified the best method of gaining success: youth development. It is after all the reason why Germany won the World Cup and England continually struggle on the international stage.

Football has long been an obsession in China and the country’s persistent failings have been something of a sore spot, which Western audiences are often unaware of. There have been times where the national team have been forced to apologise after a particularly bad performance, and following a loss against Thailand the team bus was mobbed by angry rioters. Considering the governments hard-line stance on such actions, it demonstrates just how passionately people feel about the sport.

It is not just the public: China’s economic boom has made them a serious international player but their failings on the football pitch are seen as a source of national embarrassment. The 2008 Beijing Olympics is evidence of this, the sheer extravagance of this and the preparation the athletes had shown was testament to China’s determination to excel in sports.

This determination has spilled onto the football pitch and considering how seriously President Xi takes it, China’s determined football renaissance could yield some very interesting results.