Hamoudi Fayad writes about the Euro 2016 round of 16 clash that ended Belgium 4-0 Hungary.

Belgium and Hungary came into this game with different expectations. On one hand, Belgium tried to prove their doubters wrong by looking to comfortably beat Hungary and meet Wales in the next round. With Wilmots’ coaching credentials being questioned by journalists and fans, much of the pressure was on the golden generation of Belgium to perform when it mattered after improved performances against Ireland and Sweden.

On the other hand, Hungary’s run and near table-topping group stage performance was met with praise, but realism too. Although the scoreline doesn’t suggest how close the game actually was, Hungary lacked what stopped them from topping their group and sufficiently challenging Belgium with a close scoreline: coordination.

Belgium: 1. Courtois; 16. Meunier; 2. Alderweireld; 3. Vermaelen; 5. Vertonghen; 4. Nainggolan; 6. Witsel; 14. Mertens; 7. De Bruyne; 10. Hazard; 9. Lukaku.

Hungary: 1. Kiraly; 2. Lang; 23. Juhasz; 20. Guzmics; 4. Kadar; 8. Nagy; 10. Gera; 14. Lovrencsics; 16. Pinter; 7. Dzsudzsak; 9. Szalai.

Belgium’s starting line-up wasn’t surprising, although another combination was placed on the right hand side with Meunier and Mertens, the latter in place of Yannick Ferreira-Carrasco. Movement from the full backs was quite often towards the centre, with them occupying the half spaces for the most part.

Hungary shifted the defence yet again, with Lang moving to right back and Kadar occupying the left flank. Pinter moved to central attacking midfield in a more unorthodox role while Gera moved between both defensive and attacking midfield lines across the course of the first half.

Passive press from both sides; different outcomes

Both sides didn’t use their forwards to press effectively, leaving the centre backs and defensive midfielders time on the ball. This affected the patterns of both teams, especially Hungary who seemed to have failed to make use of the lack of pressure. Adam Nagy, the young defensive midfielder who starred for Hungary across the tournament, completed 94% of his passes on the night. His passing involvement included backwards, horizontal and later on vertical passing when the creative burden was passed on to him.

Nagy’s backward movement to facilitate the progression of the ball across the pitch was met oddly as the Hungarian defenders didn’t coordinate their movements relative to his. If Nagy evaded light pressure with his back to goal, creating space in the process, Guzmics would release the ball to the poorly positioned Lang high on the right flank.

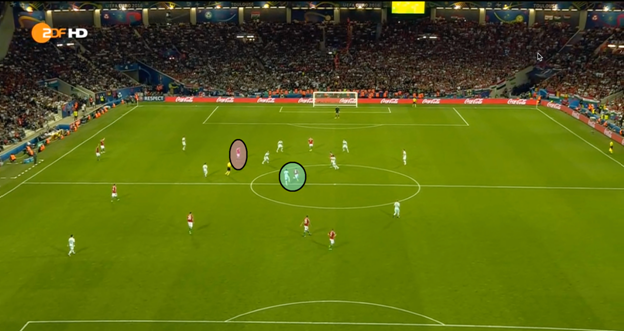

Lang positioned far away from any Hungary player on the left side of the picture (right side of the pitch).

This is where Hungary lacked coordination. With Gera moving into the next line of attack and Nagy supporting the centre backs, there were no figures in the half space to connect Lang and Guzmics. Lang’s positioning wasn’t effective either; he was barely able to form moves alongside Dzsudzsak due to his uneasiness on the half turn.

Hungary were lacking ideas in attack leading Storck (or Nagy) to make his moves early. Nagy, not known entirely for his verticality, started driving forward with the ball to create connections with the attacking midfield trio. Gera was missing in the build-up, Lang was isolated from the rest therefore someone from the Hungarian squad had to step up. Step forward Adam Nagy, who used his nimble figure to ooze past Belgium’s midfield and link up with the trio ahead.

When this didn’t work to full effect, Balasz Dzsudzsak dropped into defensive midfield during the deeper build-up play of Hungary. Oddly, this didn’t inject pace and verticality as some would have thought. Dzsudzsak used hand gestures and his experience to ensure smooth movement of the ball along the back line. Whereas Belgium were dominating the ball for the first half, Dzsudzsak’s backward movement, which started around the 37th minute, helped the Hungarian defence complete the simple tasks. This also in turn played a role in the defensive structure in the case of losing the ball, which I will talk about later on in this article.

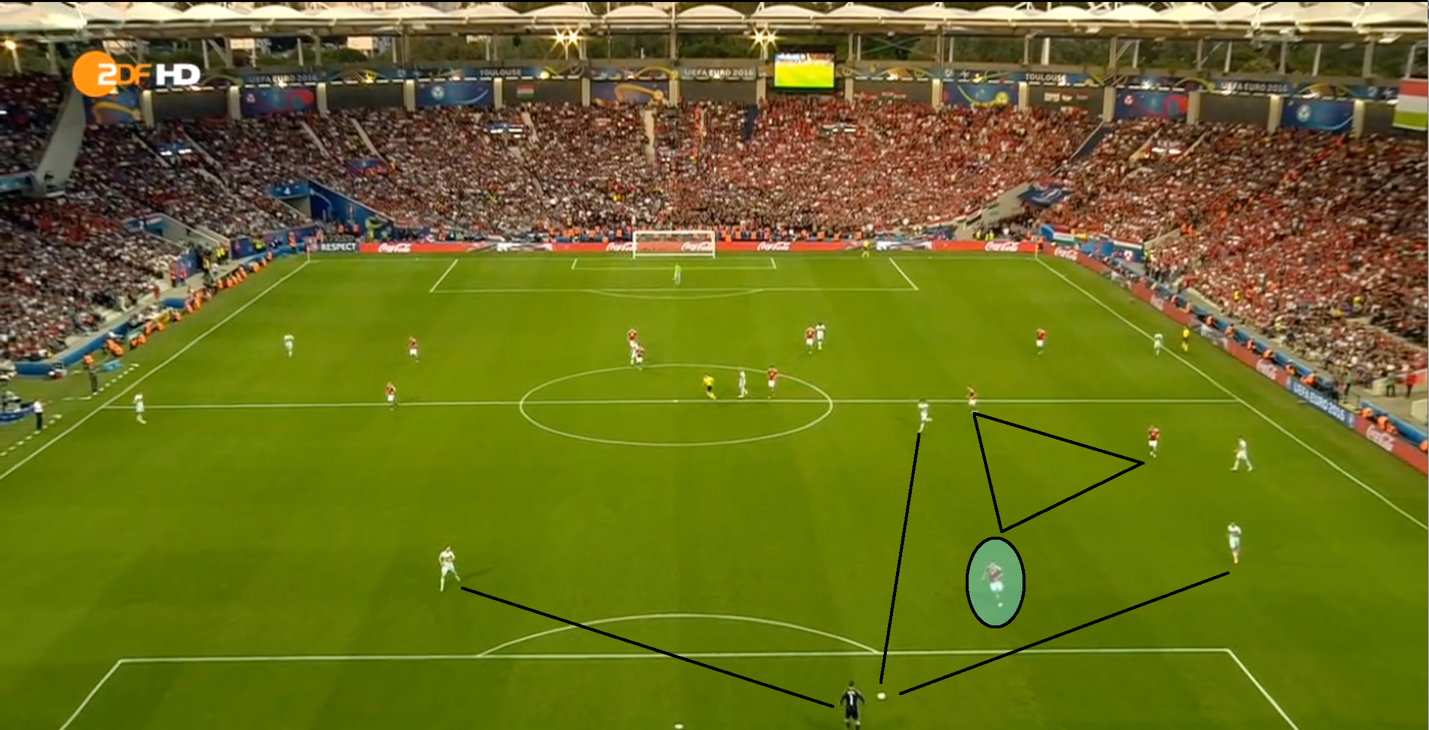

Meanwhile for the Belgians, the lack of pressure from the front line was beneficial. Even when Szalai did press the centre backs, his cover shadow was non-existent and his overall movement lacked pace and intuitive movement to gain access to the other centre backs. This could also pertain to the rest of the Hungarian attack.

Szalai, in the blue circle, cover shadowing his teammates rather than Courtois’ options for Belgium!

Belgium’s back four had the ability to use the ball to great effect, with their degree of skill on the ball very high for ‘defenders’. Vertonghen and Meunier found a myriad of space in between the lines of Hungary, preferring to progress through their lines and link up with their wingers which they found an easy task to do.

Belgium’s versatility in progressing throughout the pitch was visible. Nainggolan also involved himself in the build-up to a greater extent than the first game against Italy, yet there were still some issues in the positioning from the double pivot. There were moments where Nainggolan and Witsel were on the same vertical line which didn’t allow them to make use of the open halfspaces or flanks in the Hungarian defence.

Belgium have 9 players on the right side, with Nainggolan behind Witsel. Better positioning would have allowed Belgium to use their options more effectively and create a clear cut chance.

Hungary’s shape allows Belgian control in advantageous zones

The importance of coordination and structure in possession as well as out of possession is vital for a football team to function to near perfection. It is generally assumed that teams are more free flowing and creative in attack and tight-knit when in defence. It is true, however, that structure is also needed when in the possession phase. Structure has a connotation of defence, sitting back and playing rigidly although this is not the case.

The reason for structure being vital to teams in possession is that modern football can be decided by the art of transitions. The movement between phases in football has become interchangeable and fluid. Therefore, once in possession the team should be in a shape that has them ready to move back into the defensive shape, delay the opposition or recover the ball in the event of losing it. Hungary, although bettering Belgium in passing and possession, failed to secure these areas.

These advantageous zones or areas were the space just in front of the box – as shown in the Witsel photo above – or the halfspaces. Hungary were trying to progress through the flanks and in turn ceded control of the centre. In the process, Kevin De Bruyne had a field day – or in his terms it was just a normal match. He linked up extremely well with Hazard and Lukaku with the amount of space he was allowed in zones 14-16.

Dzsudzsak’s movement to help Nagy later in the first half helped Hungary keep a better structure. In what was a vacant central zone for Hungary, Dzsudzsak used himself as the guiding figure to prevent (successful) transitions from Belgium. This didn’t last too long.

Dzsudzsak in the light blue oval. Moves to fill in the gaps made by Hungarian midfield.

Second half developments

In the second half, Hungary came out with better coordination in attack thanks to the incoming Akos Elek. Elek sat in a double pivot with Nagy before releasing himself into the left halfspace to link up with the vibrant Dzsudzsak and Pinter.

Nagy, in the blue circle, starts becoming more of a vertical presence on the pitch and finds Elek in the halfspace. Elek proceeds to link with Dzsudzsak, who cuts inside from the left hand side. Even with Dzsudzsak’s positioning, you can see Lovrencsics not positioning himself according to Dzsudzsak’s movements.

Elek’s addition to the game also added more of a pressing knack from the centre, with his runs forcing Belgium to lose the ball in the heart of the pitch. Lukaku and De Bruyne were positioned in the right half space, possibly due to the lack of support they received from Mertens in connecting with Nainggolan and Meunier. With Hazard outside the vicinity of the Hungarian shape, Elek found it easier to press Nainggolan or Witsel with the help of Nagy marking De Bruyne.

Hungary’s central coverage also improved, however not to the extent in which it halted the threat of De Bruyne, Hazard and Carrasco at the end of the game.

Hungary dropping back into a 4-4-1-1 shape, here you can see they don’t give Mertens too many options – just Meunier behind him. If it were adjusted earlier in the game, we may have seen better access to players like Hazard in the left halfspace (right halfspace on the image) who still seems relatively free. This paid off for Belgium later on.

Belgian transitional game: the key to success

Wilmots did his homework in one aspect and it is in arguably the most important phase in modern day football: the transitional phase. The Red Devils took advantage of the lack of support to Nagy in the first half and later in the second half when Elek began to push up even further in search of a goal for the Magyars.

The pink spaces are completely vacant in terms of Hungarian player occupation. How Belgium didn’t score from this is another question, but the space Hazard, De Bruyne and Lukaku were given was criminal. Notice a pattern seen that I mentioned previously, Lukaku moving to the right half space because of the lack of support from the right hand side. Meunier too deep and Mertens deeper than Witsel.

Another occasion in which this occurred is below, however the lack of support from Belgium’s players offensively led De Bruyne to turn around and make a backwards pass. This was of no benefit to Belgium who failed to add to the scoreline in the process. Hazard and Lukaku as usual were near De Bruyne, but Mertens was down around the right back zone isolated from the attacking phase.

When Carrasco came on – a player who developed under Diego Simeone over the season – Belgium’s counter attacking play became dangerous and effective. His late addition into games has proven pivotal for both Simeone and Wilmots.

Straight from the kick-off, Hungary looked to lessen the deficit after Batshuayi’s tap-in. Little did they care about structure in this knockout match, which resulted in De Bruyne and Hazard enjoying the benefit of acres of space to score the 3rd. Hungary’s shape before the 4th goal explains their issues across the last two matches and why they conceded 7.

Nagy with no support, as usual, and Hungary’s players centralized in one area with no supporting players in the cases of any switches of play.

Conclusion

Belgium didn’t win as comfortably as the scoreline suggests and their attacking play is still very much lacking. That was the main reason they failed to bypass a great position-oriented Italian defence. Wales is another 3-man defence they will face. If the Belgians are able to exploit their transition between the 5-3-2 and 4-4-2 they may find success in reaching the semi-final.

Written by Hamoudi Fayad

- Hipster Guide 2016-17: Bayer Leverkusen’s tactics, key players and emerging talents - August 25, 2016

- Talent Radar: Saudi Pro League 10 Young Players (U-23) to Watch in 2016-17 - August 23, 2016

- Dry Grassroots: Youth Football Deficiencies in Western Asia - July 19, 2016