Sauharda Karki writes about Mourinho’s tactics in midfield and how they will differ from those of van Gaal.

Another season, another manager, and yet another tactical system. The last few years have seen the team move on from the cross-oriented direct Moyes system, to the ball-retention oriented approach of Louis van Gaal, and now the compact, perhaps pragmatic, Mourinho philosophy.

This article will aim at highlighting the key aspects of the tactical transition this year, with a lot more emphasis on the midfield and buildup, and the switch to the two-man midfield.

LvG, possession football and the 3-man midfield

With a philosophy built around ball-retention and quick transition from defense to buildup play, van Gaal more than often implemented a 3-man midfield approach to equal or outnumber the opposition in the middle third. One of the three positions served as an anchor, allowing the centre-backs to spread wider and the fullbacks to push up and supplement the midfield in the ball-retention and buildup process.

Even with the occasional 4-2-3-1 with Ander Herrera in attacking midfield, LvG often had Juan Mata dropping into central areas from the right flank to form a 3-man midfield during buildup.

The system did work wonders in its primary goal of ball retention. However, the tactical discipline imposed by the manager, especially on the midfield, proved detrimental and the possession more than often failed to produce end results. Teams with compact shape that sat deep were often hard to break down even with surplus possession. Moreover, problems in the transition back to defense left the team vulnerable on losing possession during the buildup phase.

Many have voiced concerns that Mourinho’s tactical approach may be quite similar to LvG, probably denoting the discipline imposed by both managers. However, the discipline applies to certain specific roles and situations and bears quite a few differences to LvG’s methods at Manchester United.

Mourinho’s 2-man midfield

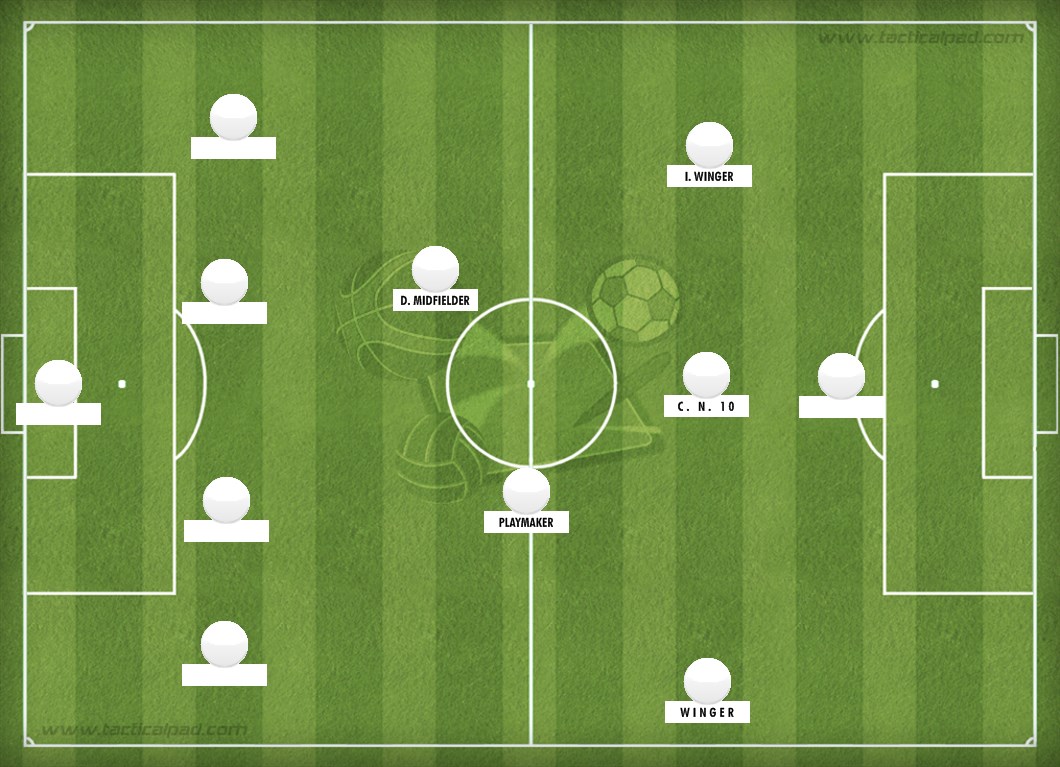

The immediate difference to be noted comes from the midfield ideology. The season will more than likely see the team transition back to a midfield pairing. The set-up in midfield constitutes a deep seated playmaker and a more defensive midfielder oriented with ball-wining and occasionally with tempo control. Most long balls come from these deeper areas.

The stable positioning also means a lot of the ball will be filtered through this area, which differs from LvG’s system where the center-backs saw a larger portion of the ball in the build-up and were often involved in recycling. The spacing between center-backs is less generous and alongside the two central midfielders the central areas are kept compact and systematic in all phases.

With deeper positions in the central area, there will most likely be an increase in the portion of tackles made by the midfield duo in central areas, with the tackles in wide areas mostly covered by fullbacks.

To complement the compact approach and deeper positions taken by the central midfielders, Mourinho often bears preference to defenders with adequate ability in the air alongside good on-the-ball approach and positioning (This may put to question Blind’s role as CB in his system, who although bears phenomenal tactical awareness in defensive areas, lacks credible aerial ability). The transition to defense on losing possession is also a lot quicker than the predecessor’s system, implying a probable reduction in the number of chances given away to the opposition in transition.

The positions that see most of the ball are the deep-seated playmaker, the No.10 and the inside forward on the left flank. Unlike van Gaal’s midfield which utilized the more technical aspects of the midfielders for possession control, Mourinho’s midfield setup emphasizes transitional mentality, proper positioning in various phases and also requires the midfielders to possess adequate physical capabilities. The fact that Mourinho’s system relies on mental aspects and tactical understanding that the players bear serves as an indicator that it may be some time before the players completely adapt to the set-up.

In the modern tactical era, a working midfield pairing is often difficult to set. With Mourinho, we have seen the ideology work on many occasions.

Real Madrid 2011/12

The team set up with Xabi Alonso in the playmaking role and Sami Khedira placed slightly more defensively.

Alonso made 9 assists that season, and had competed more passes on average than any other player in the team, averaging over 80 passes per game (atleast 20 passes more than any other player).

Alonso also averaged the most number of long passes (9 per game).

Both Khedira and Alonso ended the season with considerably high pass completion rates (88%).

Together, the duo also contributed an average of 4.6 tackles per game, the same as that totaled by Ramos and Pepe.

Chelsea 2014/15

Chelsea played most of the season with Matic and Fabregas filling the two midfield spots.

Fabregas made 18 assists in the season, completing an average of 80 passes per game (20 more passes per game than any other player on the pitch).

Fabregas averaged the most number of long passes in the team (5.5 per game).

Together, Matic and Fabregas made an average of 6 tackles per game, while John Terry and Cahill together averaged 2 tackles per game.

On both occasions, the midfield duos had phenomenal seasons and pivotal roles in their team’s success.

The 3 behind the striker

The disciplinary sacrifice made in terms of the midfield duo for defensive and transitional stability is compensated for by the three players behind the striker (a winger, an inverted winger/inside forward, and the No.10 role). These three are required to bear most of the technical burden of the team in build-up play, and elevate game tempo when required.

Wide Play and Chance Creation

On a gross analysis of chance creation in Mourinho’s system over the years, the right side of attack seems more involved in delivering crosses to the attackers while the left side involves more link-up play and short-pass play around the edge of the box.

The inverted winger and left fullback often link up with the Center Forward and No.10 with shorter passes to create chances. On the other flank, the right full-back and winger pair up to get deliveries to the attackers. The approach recently saw success at Chelsea with Hazard/Fabregas on the left and Ivanovic/Willian on the right.

Another aspect where the system differs is the very structured and traditional link-up in the wider areas of the creative third. The full-back link-up is most often restricted to involving the winger and fullback, which is unlike most modern systems, such as Pochettino’s, where the deep playmaker and attacking midfielder are more involved in the wide link-up. The approach keeps central positions more stable, and additionally allows the No.10 to take up attacking positions to supplement the Center Forward’s presence.

Although the restricted link-up has often been seen to make the attack predictable, it serves a crucial role in strengthening the basic ideology of transitional stability. The restricted linkup keeps the midfield in stable positions throughout the build-up phase no matter which area of the pitch may be involved in attack. This ensures a smooth and often quicker defensive transition with less players caught off position when the ball is lost in the build up phase and reduces the number of chances conceded due to poor or slow defensive transitioning when possession is lost. This was a problem often seen with LvG’s system, where the players were required to deviate from shape to break down a compact opposition and often caught off-guard in transition when possession was conceded to the opposition.

(The No.10 and Center Forward also have a different role than the previous season, but are beyond the scope of the article.)

Conclusion and Probable Issues

The difficulty with the two-man midfield will most likely arise in the selection process for the roles. The past few years have shown a number of instances where decent players in wrong roles have seen the team suffer tactically.

Toni Kroos, although brilliant in the passing and creative department, has often failed to pitch in and impose himself defensively, which may have been a significant factor in Real Madrid’s tactical struggle. Another instance is where Fabregas’ role had to be changed from a deeper role to the No.10 position by Mourinho, who was most likely worried about Fabregas’ positioning and movement into pockets in build up play, leaving the team vulnerable in transition.

As mentioned earlier, the midfield system is also expected to take a longer time to adapt to and may appear leakier than expected over the tactical transition period.

If things were to go wrong, fingers would most likely be pointed at the formulated approach and the place of well-disciplined approaches in top tiers may be put to question in today’s constantly evolving tactical era. However, from a tactical standpoint, the transition to the midfield-duo ideology may be one of the most intriguing things about Manchester United this season and may even see certain players perform better than last season in these roles.

- Premier League: The Growing Trend Of Counter-Attacking Goals - June 11, 2020

- Analysis | Three Things We Learned: NorthEast United 0-1 Bengaluru FC - December 9, 2017

- Three Things We Learned: NorthEast United 0-0 Jamshedpur - November 19, 2017