Ross Eaton takes us through the tactical changes that Pep Guardiola has enforced at Machester City during this initial phase of his tenure.

An emphatic victory in the Manchester Derby, saw Manchester City’s strong run of form under new manager Josep Guardiola come to a peak. With their new Catalonian boss, City have enjoyed a 100% record in the Premier League this season without mentioning a couple of impressive performances in the Champions League. With the help of fellow writers, I analysed a number of Man City games so far this term, including all competitive matches:

Bayern Munich 1-0 Man City // Man City 2-1 Sunderland // Steaua Bucharest 0-5 Man City (password: 321) // Stoke 1-4 Man City // Man City 1-0 Steaua Bucharest (password: 321) // Man City 3-1 West Ham (password: 321) // Man United 1-2 Man City

As predicted, Guardiola has begun coaching City with a focus on his philosophy Juego de Posición. The 45 year-old coach has somewhat surprisingly enjoyed relative success throughout his short time at the club so far, in terms of tactical work, with what some would consider a squad not tactically aware, nor talented enough to successfully implement Guardiola’s favoured concept.

With six new additions to the first team squad, a spend of £143 million, as well as a number of others still to join the club in the coming months after being bought this summer, Pep has shown his willingness to stamp his authority on the team not just tactically, but also in terms of personnel.

The formation selection of Pep Guardiola has remained consistent so far, with him clearly identifying a ‘W-M’ 4-1-4-1/4-3-3 as the shape which allows for him to fit in the strongest members of his squad, whilst also implementing the tactical approach he wishes at its optimal level.

Perhaps the most spoken about position of Man City’s team this season has been the goalkeeper role. Fan favourite Joe Hart has clearly been seen as not good enough by Guardiola, particularly with the ball at his feet (key ability required for Pep’s GK), which has meant Willy Caballero has started the majority of City’s matches so far this season. He too though, is obviously viewed as not good enough, as Claudio Bravo, a master of the sweeper-keeper role, has been bought from Barcelona and is set to become first choice goalkeeper.

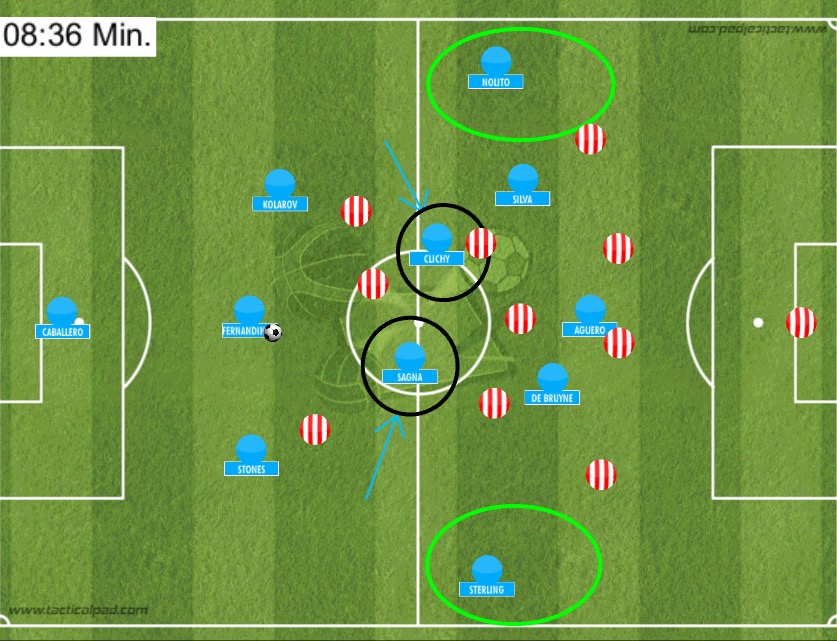

The back-four has varied throughout the matches though Pep does seem to have found six guys he likes playing, with a few of them capable of playing in a number of roles across the backline. At right-back has been Sagna, up until a hamstring injury ruled him out, with Zabaleta taking over since. 47 million man John Stones plays as the right central defender, while Otamendi or Kolarov partner him as the LCB, depending on the opposition. At left-back, Gael Clichy seems to own the first choice spot there, though again, Aleksandr Kolarov is capable of filling in when needed.

Fernandinho, for the moment at least, is the pivot of the side, operating in a 6 role in front of the centre-backs. On the right of midfield, Sterling has often started, though Navas has been given a couple of opportunities on the wing too. The right interior has been De Bruyne, the left David Silva. On the left wing Nolito has been the usual starter, though when Navas has started, Sterling has switched flanks, seeing Nolito drop to the bench. On the return of Gundogan to full fitness, things will become interesting. The German midfielder will surely be a starter, but the question is who will be replaced? Former key player Yaya Toure hasn’t seen much action, and has come under some criticism from Pep, while Leroy Sane remains out, he will also look to challenge for a starting berth on his return.

Argentinian Sergio Aguero is clearly the first choice centre forward, though off the bench, youngster Kelechi Iheanacho has excited fans with promising performances, and looks capable of at least being back-up striker.

Complex Full-Back Movements

Since taking charge of Manchester City in their English Premier League’s opening match against Sunderland, the most talked about aspect of Pep Guardiola’s City team has been the increasingly complex movements and positioning of his full-backs. Particularly during the early stages of build-up, the movements of City’s full-backs have modified according to the tactical instructions from their manager.

In the opening match of the season, versus Sunderland, Guardiola deployed full-blown inverted full-backs, with Bacary Sagna and Gael Clichy coming into the centre and halfspaces during City’s build-up and circulation of the ball. The frequency of the inverted movements of Sagna and Clichy were to the extent of Phillip Lahm from the right-back position under Guardiola, rather than the variable movements of Rafinha at Bayern which saw him able to occupy either the halfspace or the wing, still an inverted full-back, though not making as many inverted movements as Lahm was often instructed to.

We can see above that Lahm’s movements were more focused around connecting with the centre from the right halfspace, or even connecting with the opposite halfspace from central spaces. Rafinha however, was primarily based in the right halfspace and focused on connecting the centre with the right winger. Sagna and Clichy’s roles were far more similar to Lahm’s, in terms of the proximity of their movements to the central spaces. Despite this, the pair were not restricted to the centre, and often only moved into their halfspaces, providing connections to the wings.

Against Sunderland, City’s ball-near FB would position himself in the halfspace, while the ball-far FB would be in the centre, close to the opposite halfspace. With Fernandinho dropping in between the CB’s, this situationally formed a 3-2-4-1. One impact of the full-backs moving inside, against Sunderland’s man-orientation, was the creation of 1v1s on either wing. Due to Moyes implementing a man-orientated reference at Sunderland, Watmore and Gooch would follow Clichy and Sagna into the centre. Sterling and Nolito would remain wide, right on either touchline, against their single-markers, Van Aanholt and Love.

In these 1v1 situations on the wing, City had clear qualitative superiority. If superiority is not achieved in the seconds leading to the 1v1 taking place, as well as in actual the 1v1, these situations are pretty useless. Qualitative superiority is fundamental in a 1v1. By having qualitative superiority, this automatically puts the defender in a negative position. To make full use of this though, spatial superiority in other zones on the field must be achieved in order to smoothly connect with the zone where qualitative superiority is held. The positioning of Sagna and Clichy in the halfspaces meant connectivity with the wings was extremely smooth and quick the majority of the time. During ball-circulation, City would often slowly, horizontally circulate over to one flank, to manipulate Sunderland’s shape into overcompactness, then quickly switch the ball through the IFB in the centre/halfspace, who then connected with his near wing. This method of horizontally circulating onto a wing, to manipulate the op position’s shape and open the other wing, creating 1v1s in a situation of qualitative superiority was often used by Guardiola at Bayern. His Bayern team would often position players in either halfspace against man-orientations to ensure the closest player to the opposition’s full-back was unable to support them in defending the wing, as they had to mark in the halfspace. A 1v1 was therefore created on the wing.

Above is an example from Bayern’s 7-1 victory over Roma in a Champions League match last year. Though not using inverted full-backs, the outer CB’s and CM’s provided connections with the wings, as well as manipulating the man-orientated shape to create 1v1s on the wing. This was one of Robben’s best performances in a Bayern shirt.

As the gameweeks have gone on, we have already seen a few different variations of complex tactical movements from Guardiola’s full-backs. In the first Champions League match against Steaua Bucharest, there was a modification made from the Sunderland game to the full-backs’ positioning. Rather than both FB’s always moving inside, the ball-near FB would remain closer to the touchline, while the ball-far would come into the halfspace. By doing so, this allowed a wider range of zones to be occupied at once, this manipulating the at-times high press of Steaua, whilst maintains connections through the opposite halfspace to the opposite wing, by using the IFB in the halfspace.

In matches other than these, the full-backs have been instructed to make more variable and free movements, usually decided by the way they interpret a situation themselves, rather than set movements from the coach. Inverted movements into the halfspaces are frequent, while longer movements into the central space can sometimes be seen, though aren’t as common as they were in the first gameweek.

Wing-Play, Combinations and Cutbacks

Following a successful reign of quick, short passing with a focus on attacking through the centre, Guardiola modified his approach to suit the talented squad at Bayern to work to the best of their abilities. A heavy wing-orientation was often in place, with the degree of focus and effectiveness of it varying depending on the opposition. At Manchester City, it seems he has found his comfort zone somewhere in the middle. Though City have utilised 1v1 situations on the wings frequently in the early weeks, with strong connectivity to the wings being a large factor in the team’s game model, but City don’t have such a heavy wing-orientation as Guardiola instilled at Bayern.

Manchester City’s play isn’t restricted to only their wingers. Despite them creating lots of 1v1 situations for their wingers through movements away from the wings, City players also make movements onto the wings, to support the wingers in a number of ways. First of all, I will talk about the horizontal and diagonal movements of City’s interiors onto the wings. When City’s wingers are on the ball, if it is a slow attack that looks like it isn’t going anywhere, De Bruyne/Silva will move closer to the ball. By holding the ball up without advancing close to the touchline, this will draw the opposition FB towards the wing out of position, this opens up space behind him. Due to being close to the wing, De Bruyne/Silva will make a quick movement which due to their dynamic superiority, due to their previously purposely slow movement, is difficult to track.

Remaining on the topic of dynamic movements from De Bruyne and Silva towards the wing, the pair not only exploit large open spaces on the wing, but also moved into small spaces near the wing to use their nimble abilities to combine with the wingers and access space in dangerous areas. Again, when an attack seems to be dead on the wing while Sterling/Nolito is in possession, De Bruyne/Silva will move over to create a strong possessional structure in close proximity to the ball in order to escape the situation and connect with an area where City have better spacing and dynamics.

In the short training videos we have seen from the official Manchester City YouTube channel, it is clear that Guardiola will be utilising similar, previously proven training methods to ones he used at previous clubs. The famed ‘Rondo’ drills can already be watched online, enjoy this video below;

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FhEU2hqRVE8&feature=youtu.be

These Rondos develop a number of qualities, both individually and collectively. In a tight space where touches of the ball are limited, technical ability and combination play in tight areas are developed. As well as this, tactical elements such as taking advantage of numerical superiority and generating and finding the free man in sub-areas are are briefly looked at.

One chance creation method which City have frequently utilised under Guardiola has been the use of cutbacks. Due to the lack of aerial ability in City’s main striker, Sergio Aguero, low, driven balls into the box are far more effective than a high cross where Aguero is required to challenge a tall, strong, typical English Premier League centre-back. From the byline, where the wingers, as well as the interiors will often make darting runs to following a one-two to open space in behind, low cutbacks to a late runner around the penalty spot can be a method used to create some of the most simple goalscoring opportunities.

The benefits of a cutback can be huge, if executed correctly, at the correct moments. Not only is a flat pass typically easier to control and work with than a high cross, it also often provides dynamic superiority. With opposition defenders naturally being dragged towards the ball, or closer to their goal line, in anticipation of defending a floated cross, this opens space for the receiver as well as meaning they are moving away from the eventual receiver, expecting it to be crossed closer to their goals and with some height. With the defenders moving away from the receiver, when the cutback is played to a different receiver expected by them, they are unable to readjust their body position and body weight to react quickly enough to effectively defend the ball, giving the attacker a valuable second to carefully place the ball.

Roaming 8’s – ‘The Space Investigators’

In Kevin de Bruyne and David Silva, Pep Guardiola possesses two dynamic 10’s not typical or similar to the central-midfielders Guardiola has had in the past. Two world-class players, De Bruyne more of a ‘false 10’ type, Silva a dynamic, yet intricate needle player. Pep Guardiola has altered the roles of the pair to more variable, dynamic roles from the 8 positions in order to fit his ideal style of play.

Playing as left interior, David Silva has found himself in perhaps the most variable role he has ever played in despite his legs seemingly being in decline at the age of 30. Perhaps the most unfamiliar new duty adopted by the Spaniard is his dropping movements to aid the early phases of build-up from deeper positions. Starting from 8 or even 10 positions, Silva often makes dropping movements onto the same vertical line as the full-backs. He must be careful as to not drop too deep, as he cannot impact the game in advanced areas if he starts from such a deep position. As well as Silva making dropping movements, he often makes vertical movements to help occupy the opposition backline. This is done so less frequently, as it leaves De Bruyne to help build through the centre, not the Belgian’s strongest area. In terms of finding pockets of space, a key aspect of Silva’s performance due to his tactical and technical intelligence, operating between the opposition backline and first midfielders lines is important to his own and his team’s performance.

In order to create space for Silva to work in, Aguero makes lots of vertical movements to stretch the opposition backline. De Bruyne too helps by making horizontal movements into the right halfspace, to open the centre more for Silva, should an opponent follow him towards the right. Inverted movements from the full-backs can also be helpful for generating some space in between the lines, as their central positioning may draw opposition midfielders out of position towards the IFB’s, leaving Silva free between the lines.

“I have to help in build-up play more often and sacrifice a bit more in defence.” – David Silva on his new role.

Silva’s midfield partner Kevin De Bruyne has a role similar to Iniesta’s at Barcelona under Guardiola, though as right interior rather than left. Rather than being tasked with making dropping movements to aid the early phases of build-up, De Bruyne plays a more horizontally-orientated role, making alternating movements with Sterling to and from the right wing, with the objective of generating a free man due to the quick, confusing movement.

As well as these horizontal movements, De Bruyne also works in between opposition lines, making short horizontal movements from centre to halfspaces or vice versa, in search of an open passing lane. Another role De Bruyne shares with Silva is the occupation of the opposition backline. Due to De Bruyne’s lack of quality in early phases of build-up he is often the CM tasked with finding space between the lines or pushing up alongside Aguero onto the last line.

Pushing up onto the last line while Silva drops deep can cause a few issues with the possessional structure, largely down to the lack of central occupation. Though not too noticeable due to City’s territorial dominance within Steaua’s half, in the first leg against the Romanians, City encountered some issues in terms of progressing through the central areas from a build-up beginning with Caballero. When the ball was in the centre and there was no inverted movements from the FB’s, David Silva often dropped deep. With Silva vacating the 8 position, this left De Bruyne as the sole City player occupying the 8 or 10 spaces. Lacking some intelligence in terms of spacing, De Bruyne often occupied the 10 space during phase one. Though he attempted to move horizontally to find an open lane, this left the CB’s with no viable option as even if a lane opened up, De Bruyne was too large a distance away, making the line breaking pass very difficult to play, and easier to intercept.

Implementation of Juego de Posición

Arriving slightly earlier in Manchester than expected is Pep Guardiola’s favoured footballing philosophy of Juego de Posición. After just a couple of months at the helm of Manchester City as well as considering just a single month of this was working with his full squad, Pep Guardiola has had some surprisingly very positive results in terms of the implementation of his positional play game.

At Barcelona it took around three months before clear signs of Juego de Posición being successfully implemented showed, at Bayern between three and four months for signs with it being over a full season before it was being utilised with excellent effects and now at Manchester City, it seems as if either Pep has streamlined his training methods in order to make the transition into the method of play smoother or his Man City squad have simply adapted very well, better than his Barca and Bayern squads. As always, the training drills used by Pep Guardiola are football-specific, and to as much of a degree as possible, game-realistic. In order to make it as easy as possible for his players to take the positional play instructions from training into a game, drills must be set-up in a way that the situation could occur in a game situation and the players must be able to deal with it effectively using the instructions given.

Preventing isolation by getting numbers around the ball to support it, particularly in the first phase where losing the ball is most dangerous, is a principle of positional play. This has been worked on in training, where City have practiced vertical passes to escape immediate pressure on the ball with the closest players making supporting movements towards the ball to create a strong structure to escape the second pressing wave. City have practiced doing so by generating triangle and diamond shapes close to the ball.

More importantly than structures within sub-areas in terms of Juego de Posición is the spacing and occupation of zones. An issue that Manchester City have encountered before, it will certainly be one Pep will have to do serious work upon if his side are to effectively play Juego de Posición.

In the early weeks, things have looked promising, more so than expected at least, with a number players adapting excellently to the concept. Alongside their more effective levels of penetration and progression through smoother build-up, is the improved spacing and occupation of a greater range of zones.

By staggering the horizontal and vertical lines being occupied with adequate distances between each player, the opposition are forced to either adapt their defensive shape to mark the positional play, which leaves them stretched, or choose to stick with their shape and ignore the positional play, leaving the underloaded side of the field free for exploitation should the team be able to switch the ball quickly enough. As well as this, the staggering creates pockets within the opposition defensive block which can allow attacking players to position themselves between the lines. Finding space between the lines and generating and finding superiority from these positions are a key aspect of Juego de Posición. Though instructed to position themselves in specific zones in relation the ball, these positions should not be static and movement must be constant and fluid in order to open passing lanes and find penetrative lanes where the ball can be received.

Guardiola’s Juego de Posición does not often rush vertically and ensures that prior to progressing into advanced areas the structure is stable in preparation of both an attack and a defensive transition. Control is the key for some moments here, as the ’15-pass rule’ kicks in. Prior to the majority of Guardiola’s team’s attacks, we will see slow, controlled possession in unthreatening positions for a few seconds. This time gives players the chance to move into positions in relation to the ball, considering both the offensive and defensive possibilities as verticality begins. Once the player in possession believes a strong possessional structure has been achieved, progression may take place. From here, fluid movement and circulation should occur, in order to manipulate the opposition’s defensive shape and generate and search for superiority. Weak spots within the opposition defensive structure are likely to be found here, which will allow for early penetration, though this isn’t always the case. If the defensive structure is very strong and seemingly inpenetrable then longer passes may be used to escape the compactness and immediately in the subarea of the ball, to an underloaded area. Positioning players, ideally needle players, within the opposition block may also be used in an attempt to take advantage of qualitative superiority. If however, there are weak spots or frequent gaps within the block, the positional play will look to dominate the game using the weak spots. This area will be constantly attacked throughout the match, explaining why we commonly see Pep’s team’s with a heavy focus on a particular area (ie-wing focus).

Improved Structure Aids Defensive Transition

The principles of Man City’s positional play are having great benefits offensively, though the impact defensively is also significant.

Though a wide spacing to occupy a range of zones is key to achieving a strong possessional structure, the distances between the players cannot be too long, for both offensive and defensive reasons, with the reasons being relatively similar. In terms of attacking, isolation against a defensive overload is a difficult situation, which is why players should be positioned in the subareas around the receiver of a pass, to provide immediate support to the ball. Defensively, support is needed around the ball to counterpress effectively. Counterpressing is the immediate, intensive pressure of the ball following loss of possession. By having adequate numbers in the subareas around the ball, large distances aren’t required to be covered in order to counterpress, meaning pressure can be put on the ball at the most vulnerable time, when it has just been gained. The inverted full-backs have enhanced City’s counterpressing as the congestion of the centre makes it difficult to escape the immediate pressure. By having extra numbers in the centre, City are able to congest the location of the ball and the subareas around it in great numbers.

The possessional structure was a major flaw in City’s game under Pellegrini which had a negative impact in possession, but more so in the defensive transition. Due to the poor spacing with either too small or too large gaps in between each player’s positioning, there was often space left to penetrate on the counter for opposition attackers, through either dribbling or passing. With such an emphasis on positional play though this has been an aspect of Man City’s game which Pep Guardiola has looked to improve since taking over. Though City already look to be positioning themselves in a more effective structure, there remains some problems which Pep will have to work on to iron out. As already spoken about, De Bruyne’s low tactical intelligence can mean under-occupation of the centre, which poses large problems in the defensive transition. In the defensive transition the centre is an area where vertical passes are likely to be played through on the counter, hence why cover is necessary in the centre.

Other than ensuring the central midfielders cover the centre appropriately during circulation, another variation we have seen is inverted openers from the full-backs for their impact defensively, rather than offensively. Though the IFB’s positioning stopped opposition counter-attacks a few times when in use for attacking reasons, the first time we saw IFB’s coming inside for the primary reason of defending against counter-attacks was in the Manchester derby.

When Sterling or Nolito were in possession of the ball on their wing, rather than making a supporting movement such as an overlap or underlap, Sagna and Kolarov pinched inside into their respective halfspaces, on a similar line as Fernandinho. This allowed them to focus on defending their halfspaces on the counter, particularly against Mkhitaryan and Rooney, who love countering through these zones rather than the wings. By being initially positioned in the halfspace, Sagna and Kolarov were also able to counterpress more effectively, due to their positions typically being closer to the area of the majority of turnovers. United really struggled against the counterpressing of City, especially in the first half, when Pogba was the only player from deep who was able to offer much resistance to the pressure. This led to waves of attack on United, as the transition to attack wasn’t smooth enough for United to keep possession comfortably.

Gaining Defensive Access High Up the Pitch – The High Press

After operating in a mid block with light pressure at a low intensity under Manuel Pellegrini, it would be very arguable that the transition into more of a high-intensity pressing game under Pep Guardiola would be a difficult, slow and rough one. This hasn’t been the case however, as City’s work rate and intelligence of pressure and positioning has been superb.

We have seen a range of pressing schemes depending on the shape required to maintain defensive access against specific opposition shapes, with the main variations being the intensity and height which the central midfielders press at. Though David Silva isn’t renowned for his defensive work, whilst De Bruyne is slightly better though not amazing, the pair’s work in supporting Sergio Aguero in pressing the opposition backline has been excellent. Aguero usually presses from the centre of the pitch, arcing his run to block a pass back to the goalkeeper, whilst the ball-near CM presses from the halfspace. The ball-near winger then springs into press to either prevent a pass out to the full-back, or to press him as he receives it. This is in an option-orientated zonal coverage scheme.

Conclusion

Following an excellent start to the season, Manchester City put any potential questions over their squad’s ability to bed after a brilliant win at Old Trafford over rivals Manchester United.

The tactics of Pep Guardiola have not only been amazing to watch but they have also been effective, helping City gain results but also play in a dominant fashion. Perhaps the most impressive aspect of their control of matches has been the quick success of Pep’s implementation of Juego de Posición. Normally a lengthy process which has ineffective results early on, City seem to have adapted very nicely and are beginning to carry out some of the key principles of Pep’s philosophy to a degree of success at such an early stage in his reign.

As applies to any team though, there remains flaws in City’s game, particularly in terms of penetration and chance creation at the final ball, where Pep has openly admitted in the press that if Man City are to compete strongly in Europe this season, they must improve upon.

Taking all things into consideration though, the rapid rate of progression is extremely promising and if it is to continue at a rate anything similar to the current, Manchester City may be on their way to huge successes under their new hero, Pep Guardiola.

- Tactical Analysis: Nice 4-0 Monaco | Favre’s efficient approach - September 14, 2017

- Tactical Analysis: Australia 2-3 Germany | German Defensive Scheme - June 22, 2017

- Tactical Analysis: Napoli 1-3 Real Madrid | Napoli unable to shift momentum - March 9, 2017