Eric Devin provides a detailed tactical analysis of the AFCON Final which saw Cameroon take home all the glory.

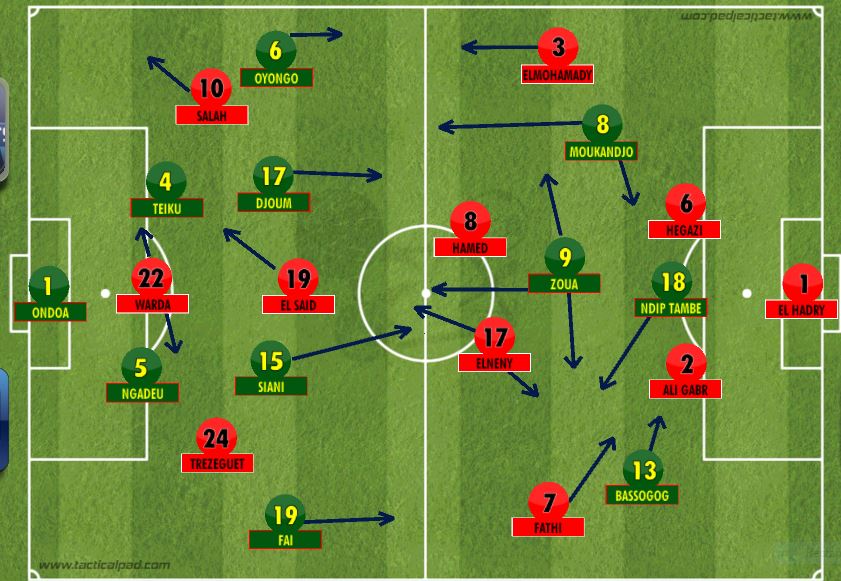

Egypt (4-2-1-3): Essam El Hadary; Ahmed Elmohamady, Ahmed Hegazy, Ali Gabr, Ahmed Fathy; Tarek Hamed, Mohamed Elneny; Abdallah El Said; Mohamed Salah, Amr Warda, Trézéguet (Ramadan Sohbi 66′)

Cameroon (4-2-3-1): Fabrice Ondoa; Collins Fai, Michael Ngadeu, Adolphe Teikeu (Nicolas N’Koulou 31′) Ambroise Oyongo; Sébastien Siani, Arnaud Djoum; Christian Bassogog, Jacques Zoua, Benjamin Moukandjo; Robert Ndip També (Vincent Aboubakar 46′)

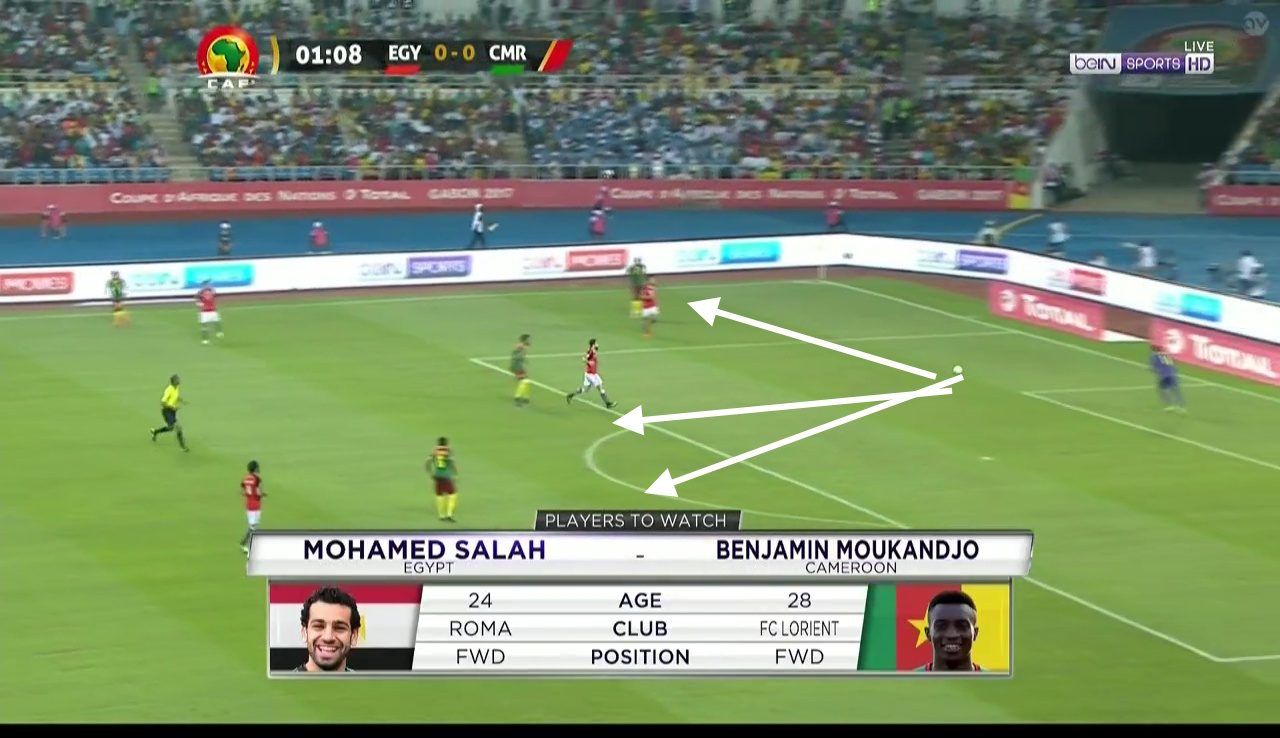

Neither Cameroon nor Egypt, despite their storied reputations, had entered the 2017 Cup of Africa Nations with any high hopes. Despite the absence of Nigeria, they were far from favorites, with the likes of Ghana and Senegal being touted as the strongest sides pre-tournament. Cameroon had been thwarted by several players turning down call-ups from Hugo Broos, including the Liverpool defender Joel Matip, but also several players with less estimable reputations, the likes of Bordeaux’s Maxime Poundjé and the young Ajax ‘keeper André Onana. Egypt had a stronger reputation, with Hector Cuper able to call on the likes of Roma’s Mohamed Salah and Arsenal’s Mohamed Elneny, but few of their players had the sort of familiarity to European audiences that one would associate with a high level of talent; half of their squad play domestically and only three are regulars in Europe’s top five leagues.

The resemblance between the two teams doesn’t end there though; both had advanced to the final by playing an overly defensive style to thwart more attack-minded opponents. Spurred on by unheralded but superb center backs, both teams saw their wingers drop very deep, pinning back opposing fullbacks and packing the box. Cameroon occasionally would spring from wide areas through their own fullbacks, but both teams employed a front four whose efficacy relied not on individual play but more on positional flexibility, creating space by strikers dropping deep or wingers cutting inside. With neither team seemingly be willing to give ground in this respect, the final had shaped up as a rather dull game, but the result was far from the truth. Cameroon’s defensive midfielders were surprising catalysts in attack and Egypt’s goal in their 2-1 defeat was scored by a defensive midfielder bursting into the aforementioned space opened up by Salah pulling defenders wide, both goals emblematic of a more intrepid attack.

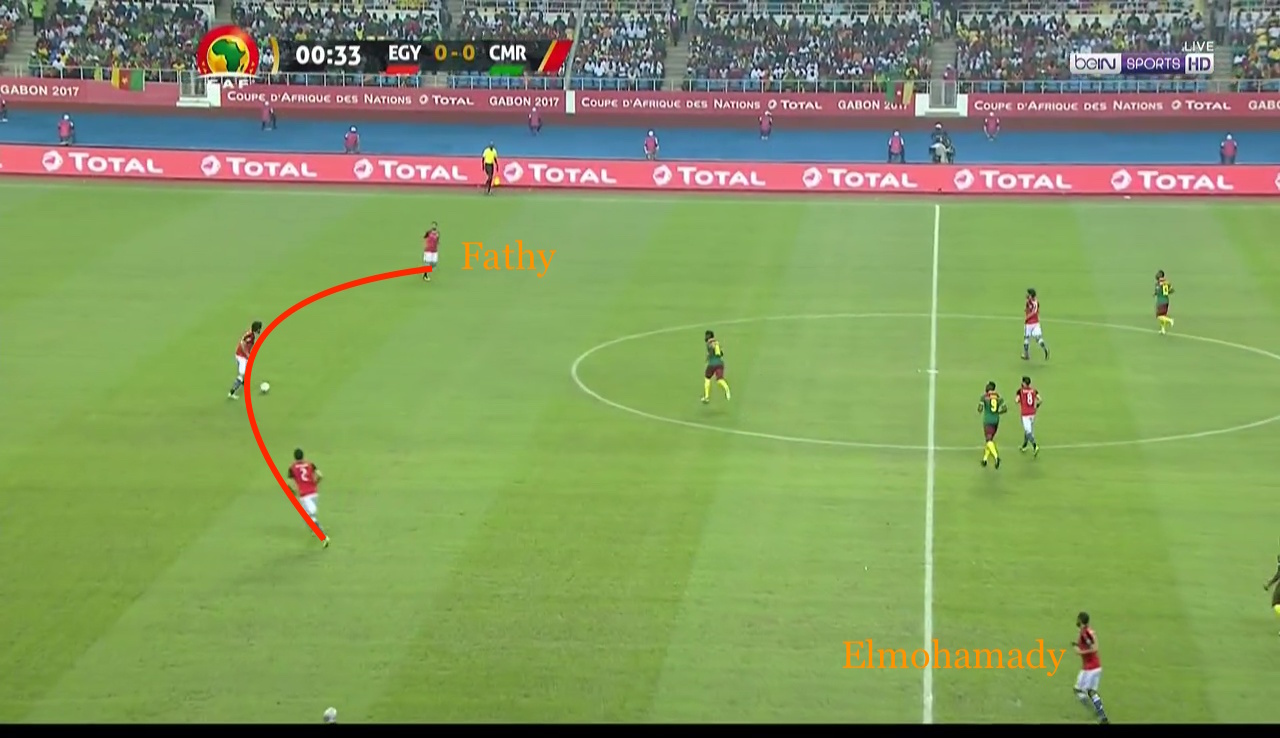

That said, the real story of the match was not the similarities between the two sides, but rather the different ways in which they reacted to the changes. Egypt nominally set up in a 4-2-1-3, with El Said sitting in front of the two defensive midfielders, but in practice, especially at the beginning of the match, the system more closely resembled a three-man defense. In the first image, Fathy, the left back, has tucked inside and Hegazy and Gabr have both shifted over. The function of this is two-fold: it primarily allows Egypt to keep possession more efficiently, as the team had run the risk of becoming exhausted by playing a high press. With more of the ball, the front four in particular would be less taxed. However, its secondary (and intentional) benefit also, in pushing Elmohamady further up the pitch in a change from Egypt’s usual deep block, was to put further pressure on Cameroon’s captain, left winger Moukandjo. Moukandjo’s industriousness in wide areas had been key to his side’s success thus far, and Hector Cuper’s strategy of pushing the Hull City man forward in an effort to give him more to think about was a good opening gambit.

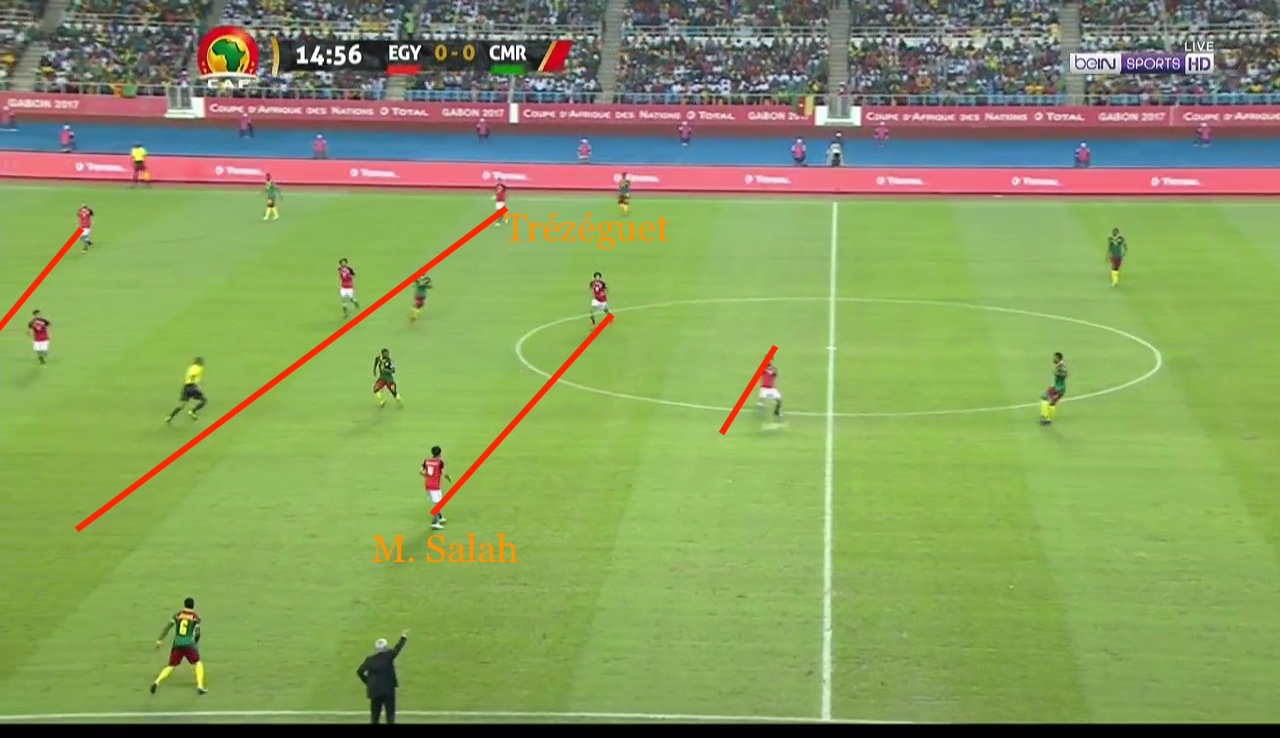

In the second image, we see how Egypt had built upon having an extra player in midfield to press Cameroon very high up the pitch. Here, early in the match, with the easy options pressed by Egypt’s attackers, Cameroon were forced to play the ball long out of the back, a once again intelligent move by Cuper. Not only is Ondoa’s distribution not the strongest part of his game, but the distinct height advantage enjoyed by Egypt’s center backs meant that the effectiveness of long balls would necessarily be limited.

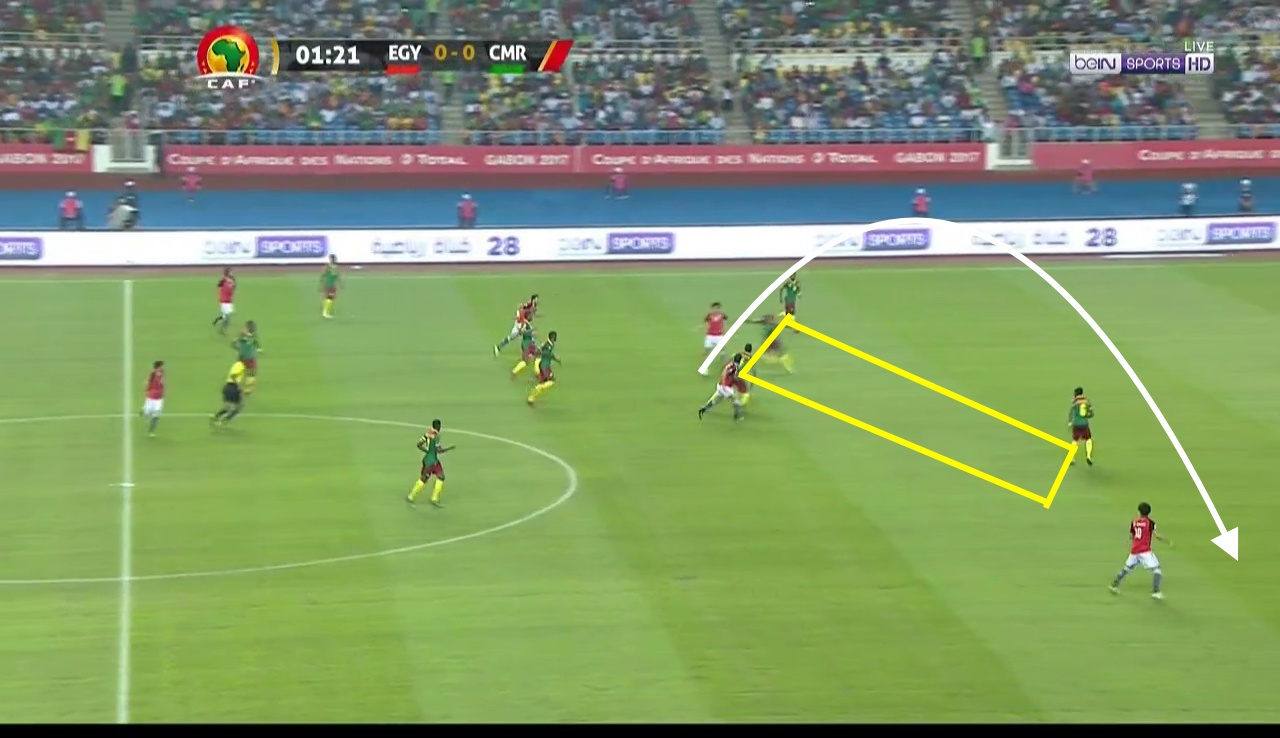

Cameroon, of course, could have done more to combat Egypt’s approach from the off. The first image shows their back four playing incredibly close to each other (yellow box), with Mohamed Salah peeling away into space. A simple ball over the top from Warda (white arrow) manages to undo the back line’s positioning; keenly aware of the pace of Trézéguet and Salah, Cameroon should have endeavored to play with a more balanced approach. This particular opportunity led to a shot for El Said which was saved; only the failure to bomb on by the fullbacks prevented Egypt from having more success in wide areas in the early going.

In the second image, we see how Cameroon have recognized this lack of defensive width and sought to ameliorate it. As previously mentioned, Moukandjo drops deep, much as he had on occasion against Ghana. This is needed, as Salah (offscreen) has moved wide, while Oyongo has moved inside to put more pressure on El Said. Cameroon’s coping here is based upon not wanting to pit the pace of Salah one-on-one against Ngadeu and Teikeu; for every one of the four Egyptian attackers, a Cameroon player that is not a center back seeks to mark them. Warda is the lone exception, but both center backs are tasked with minding the PAOK attacker, who normally plays as a winger. Thus, by effectively starting an attacking midfielder (El Said) behind three wingers and no orthodox striker, Egypt were able to easily interchange positions, pinning back Moukandjo and Bassogog, to a lesser degree and limiting their effectiveness in aiding the attack.

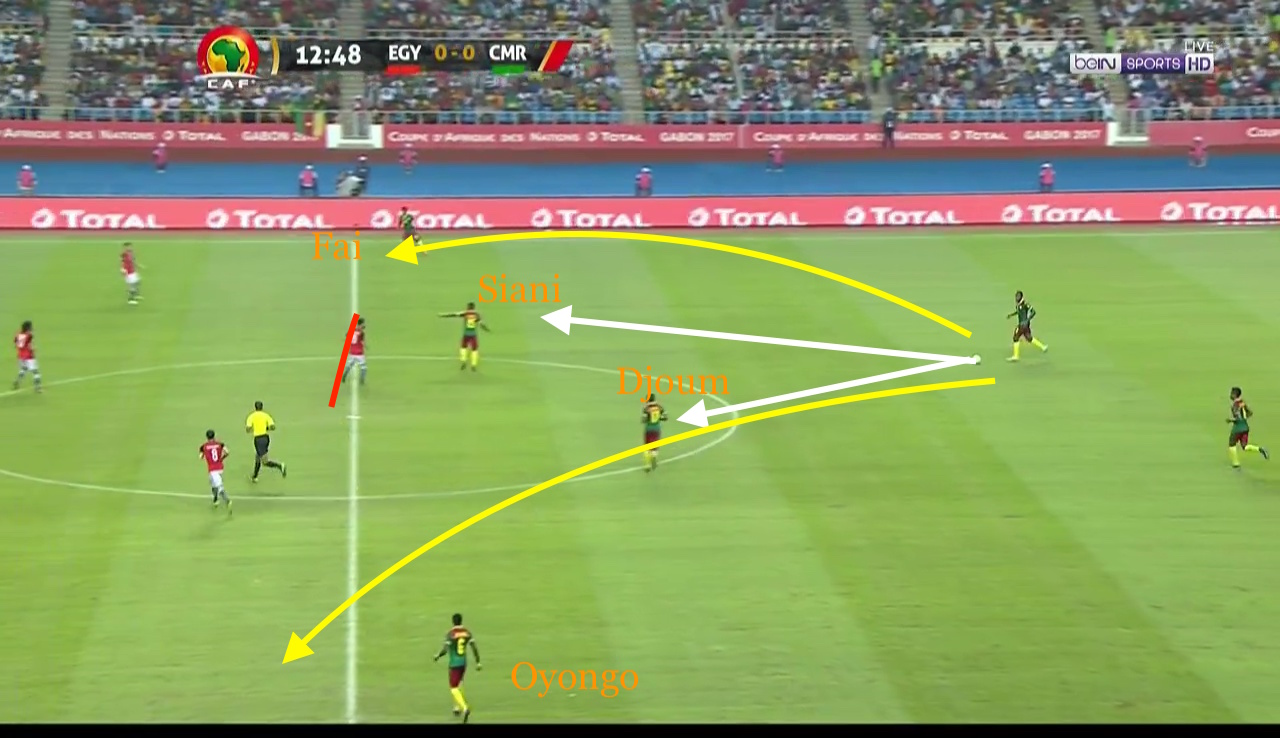

However, Egypt, despite easily having the better of the opening stages of the match, were unable to keep this up, even before scoring. Here, in the first image, just thirteen minutes into the match, the press has dropped considerably. Ngadeu has plenty of time on the ball, and Djoum and Siani are easy options for a pass at the edge of the center circle (white arrows). The fullbacks, Fai and Oyongo, are also viable options. This early drop in pressure from Egypt allowed Cameroon to not only control possession more easily but also considerably reduced the workload on the two wide players, Bassogog and Moukandjo.

The second image shows the logical progression of this as it relates to Egypt’s “three man” defense. The system thus becomes a 3-4-2-1 (red lines), with the only width coming from the bank of four in front of the defense. Salah dropped into midfield alongside El Said, behind Warda, while Trézéguet played essentially as a wingback, moving opposite Elmohamady with the two defensive midfielders positioned centrally. Again, this deep block had been effective all tournament, but usually as more of a 4-4-1-1, so there was more natural width. As a 3-4-2-1, the opposing fullbacks are given more space ahead of themselves and were unafraid to use it; Fai and Oyongo were more involved in build-up play against Egypt than they had been against any other opponent in the tournament.

Cameroon, lacking numerical superiority in midfield, also sought to involve the defensive midfielders by way of creating more options for Moukandjo and Bassogog. The two wingers, particularly Moukandjo, were keen to play a free role to act as the creative fulcrum, but they needed willing workers around them to have a modicum of success. This style of play relies on a maximum amount of graft, and was arguably the prime factor behind Ndip També being the regular starter over the more fancied Aboubakar.

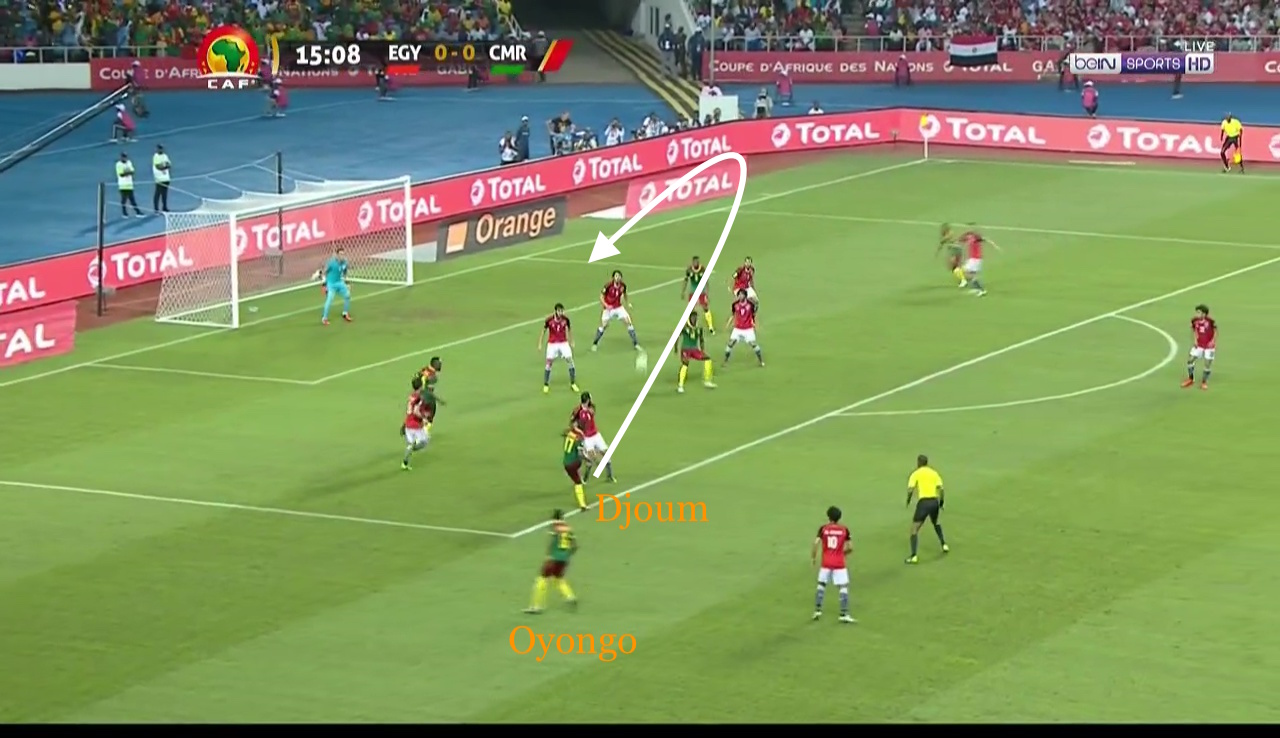

With Egypt sitting so deep and Trézéguet and Elmohamady well-positioned to limit the involvement of Fai and Oyongo in this way, Cameroon would need more from their defensive midfielders, and they got it, notably from Djoum. The Hearts man is normally a prosaic presence on the pitch for Cameroon, but is often used as a more creative player for his club. Seeing the need for another runner to create space for his teammates, he got forward diligently, as this image shows. Here, with Egypt essentially sitting in two banks of four inside the box, he is afforded space to run at the defense, with the option of switching play to Oyongo on the overlap. He chooses instead to play a cross to the back post; the wisdom of this is debatable given the aerial abilities of Egypt’s defense, but it nevertheless established the trend of Broos adding subtle wrinkles to Cameroon’s attack.

Part of the ease with which Djoum could do this was down to the shuttling runs of Zoua. While Ndip També would often peel wide, swapping positions with Bassogog or Moukandjo, the Kaiserlslautern man engaged vertically, picking up the ball in central midfield and running with it (white arrow). This led to some promising interchanges with Moukandjo in particular (second image); even though this attack wasn’t as promising owing to a lack of involvement from Oyongo, Cameroon were aiming to frustrate Egypt through an accretion of ideas. The more subtle variations that they employed, the more the Pharaohs were forced to consider. As a result, Cuper’s men retreated into their low block as a safe option, the dangerous high press of the match’s earliest stages a thing of the past.

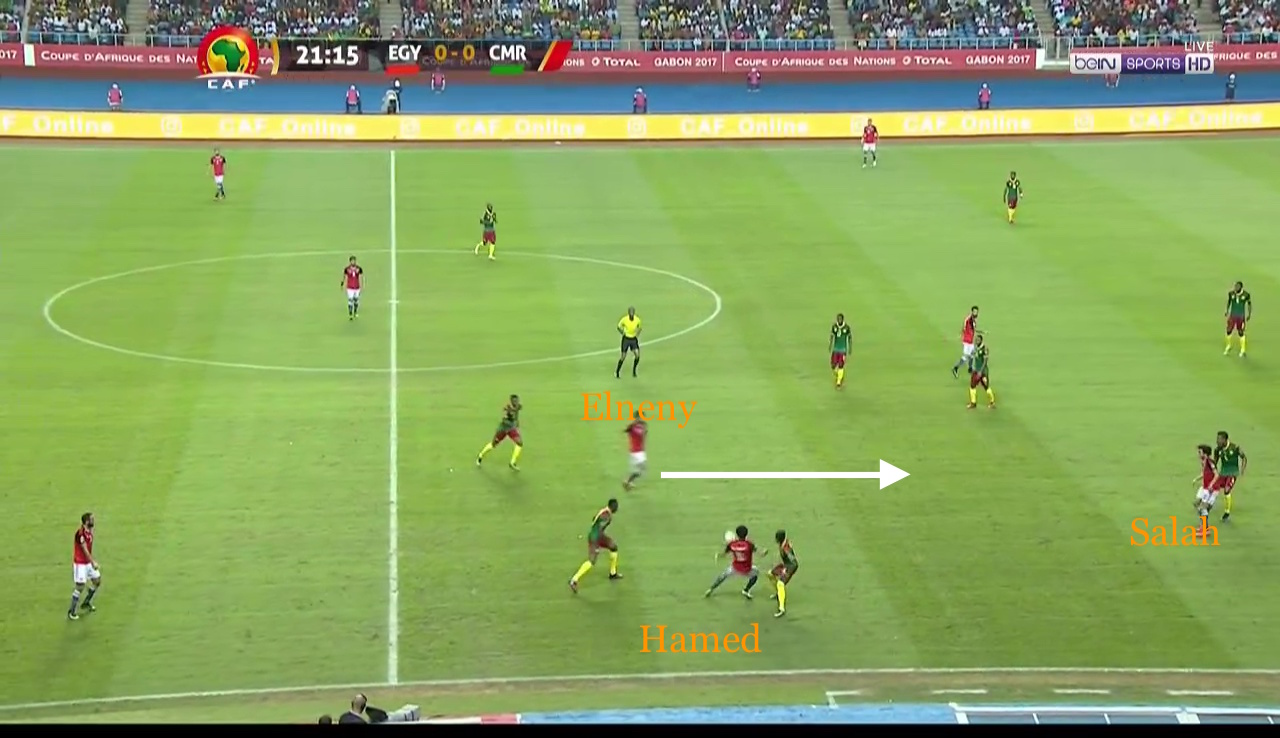

While Egypt failed to develop much of a response in defense, there was some inventiveness on display going forward, at least in the early going. Their goal, scored by Elneny, is a good example of this. The Arsenal player, much like Djoum, is generally used in a central pairing by Arsene Wenger, but he has more in his locker than crunching tackles. In the first image, Hamed has gone forward and slightly wide, drawing a double team from Oyongo and Moukandjo. Ahead of him, that has left Salah one-on-one against Teikeu, while Zoua trails behind Elneny, seemingly surprised by the midfielder’s adventurous move with Hamed likewise forward.

In the second image, we see the result of Elneny’s one-two with Salah. The Roma winger has got to the line and turned Moukandjo, who seeks to recover. Oyongo moves to pressure Salah, but because Djoum has failed to check the run of Eleny and Teikeu has moved deep to guard against a cross, the Arsenal player is thus released into the box. Elneny isn’t the paciest player, but against Teikeu, the Sochaux man will be second-favorite in a footrace, as was seen in Elneny’s move past the defender to shoot. Elneny is more than functional in this box-to-box role; while his goal represented a cracking finish, one not easily repeatable, he readily showed his attacking capabilities. This leads one to question whether he shouldn’t have sought more involvement in attack, even after Egypt had gone ahead. Given the team’s defensive record to that point in the tournament, one could certainly give Cuper the benefit of the doubt, but did Egypt shut up shop perhaps a bit too early?

This image is from immediately after the goal; Egypt retain their shape of three at the back, but it now manifests as a 3-5-2. Salah plays as the left wing-back and Elmohamady moves forward to play as a third central midfielder. This does have the unfortunate effect of limiting how involved Salah can be in the attack, but it speaks to Cuper’s confidence in his team’s system. Satisfied with the lead, Egypt move in this way to address the issues present as regards width in the 3-4-2-1, which is an intelligent adjustment on the part of Cuper. However, what is more important is how deep Egypt sit. If the press had dropped after the first ten minutes, it is now all but nonexistent. Given Cameroon’s proclivity for poking and prodding, trying different approaches, it was foolhardy of Egypt to not only change tactics but to sit so deep, gifting their opponents a shortened pitch and possession; a return to the 4-4-1-1 which was so effective against Burkina Faso would have sacrificed less from Trezeguet and Salah.

This was perhaps doubly so as Broos was far from finished in terms of changing his approach. The deeper Egypt sat, the more Cameroon took advantage, especially on the wings. Collins Fai had been far the more conservative of Cameroon’s two fullbacks in the tournament, but as this image shows, Egypt’s narrow back four(red line) (they often reverted to the aforementioned 4-4-1-1 in the second half) invites a spread of play. Bassogog has cut inside to receive the ball from Djoum, and has drawn the attentions of both defensive midfielders, as well as Trezeguet. A quick switch of play (white arrow) is all that it takes to free Fai for a cross, and with Aboubakar having replaced Ndip Tambe, Cameroon possessed more of an aerial threat in the second half.

Cameroon weren’t satisfied there, though, and Broos also had Moukandjo and Bassogog switching sides, as the second image shows. This allowed Zoua to drop deeper and make more runs from midfield, with Moukandjo playing off of Aboubakar and Bassogog working as an inverted winger. While Cameroon admittedly enjoyed less freedom with Aboubakar on the pitch as opposed to Ndip Tambe, Broos’ adding yet another twist meant Egypt had even more to consider defensively. Cameroon eventually found their equalizer, but Egypt seemed shocked by the goal. Cuper did nothing to change his tactics; his only change was to replace Trezeguet with Sohbi. The youngster’s injection of pace was a like-for-like change and did little to alter the game.

In the end, as befits an international final, two similarly placed and styled teams battled heartily. The match was, to the untrained observer, decided by a moment of brilliance on the part of Aboubakar. But, in rebuttal to that, Elneny’s goal had a similar cast to it. The number of chances created by Cameroon and with them, their eventual victory, was the product of Broos’ tactical daring. By making positional versatility the general thrust of his team’s approach, it made it very difficult for Egypt, even with their characteristic deep lying play to cope defensively with Cameroon in the absence of their initial high press. By abandoning pressure on Cameroon, Cuper had placed faith in the supreme defensive abilities of his team, a risky proposition in light of the pace and inventiveness of Bassogog and Moukandjo. It may seem cruel on the Argentine in light of a strong tournament, but Cuper’s failure to react tactically was the deciding factor in this match, making Cameroon deserved winners on the back of Broos’ imagination.

Read all our tactical analyses here.