Siyang Xu writes a detailed tactical analysis about the UEFA Champions League match that ended Liverpool 3-2 PSG.

Liverpool faced PSG in arguably the biggest match up of the opening round of Champions League fixtures. Last year’s beaten finalists did an impressive job of controlling the match, with particular focus on protecting against counter attacks from the dangerous trio of Mbappe, Cavani and Neymar, whilst still managing to create overloads in wide areas to create threatening attacking situations. The Parisians, on the other hand, struggled to get going and put on a disjointed display, struggling to find connections within their attacking play and provide the platform for their attacking superstars to flourish.

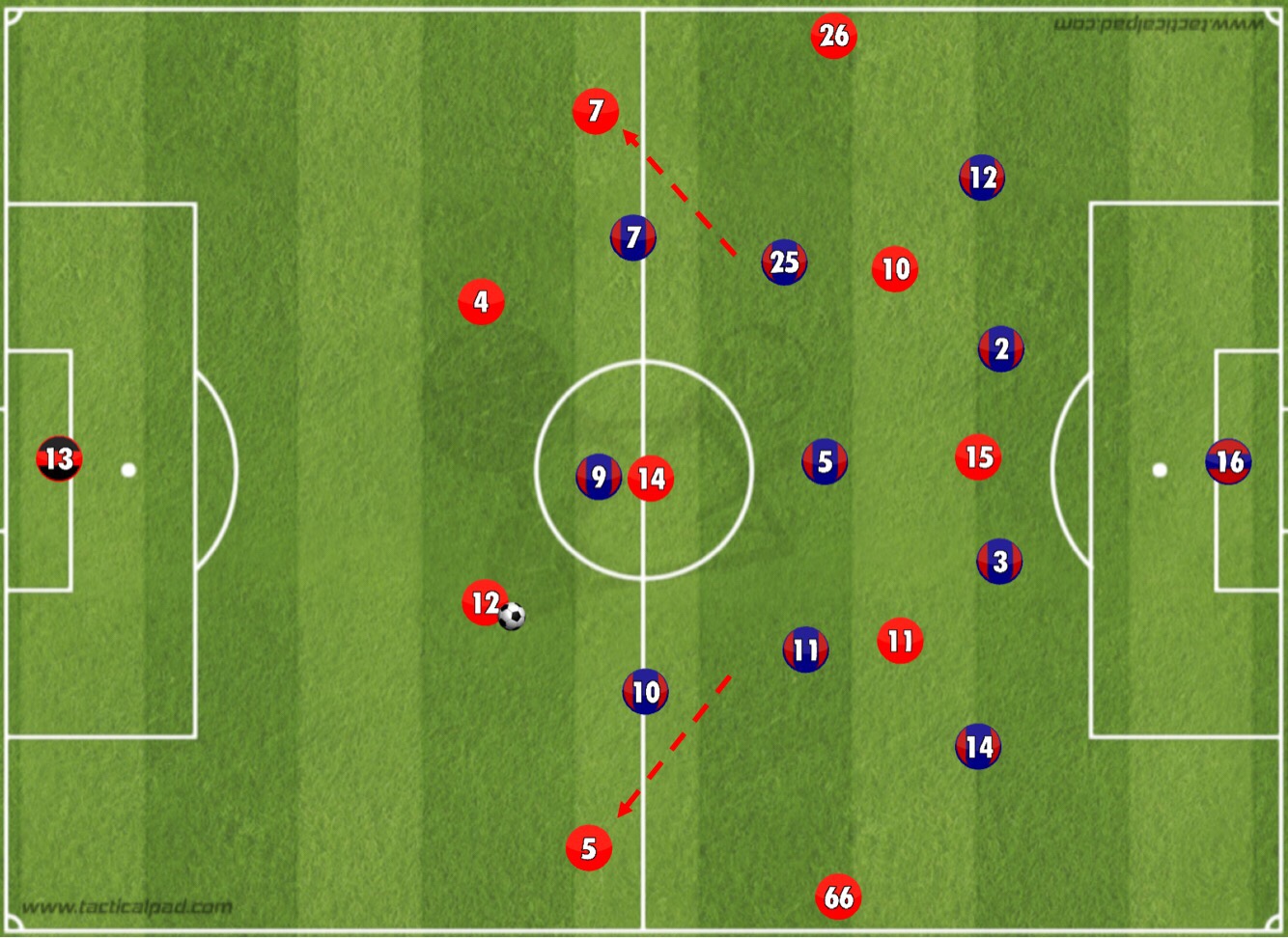

Line Ups

PSG’s Issues in Build Up

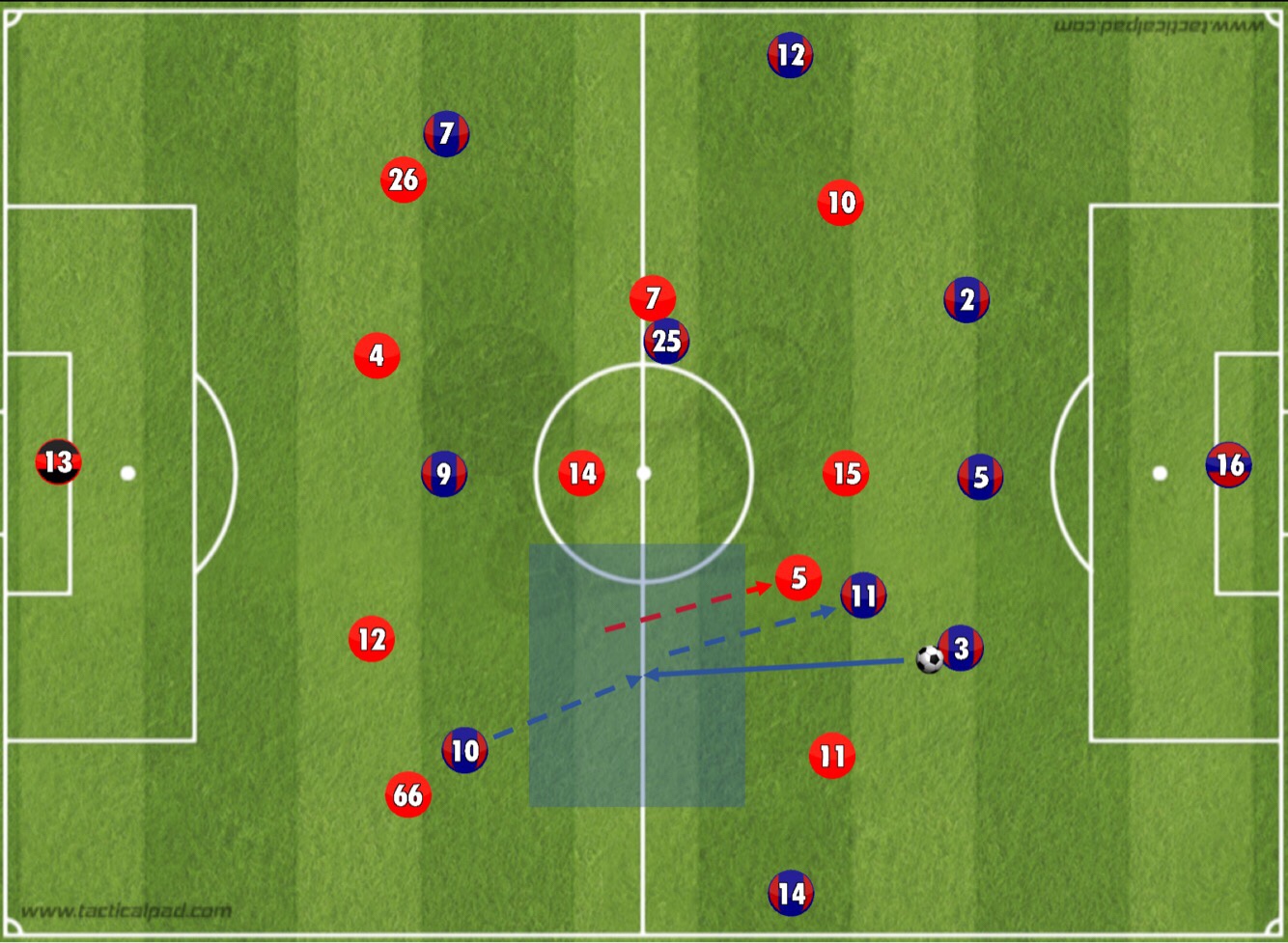

Liverpool primarily defended in a 4-3-3/4-3-2-1 mid-block, using a narrow structure and staggered lines to try and deny their opponents central space to progress the ball. An interesting ploy PSG used to try and create space was to use Di Maria as a decoy for Neymar, opening up a passing lane to the Brazilian in the process. With Liverpool’s #8s inclined to stay close to their direct opposite number, Di Maria made runs to drop deep and drag Wijnaldum with him, in turn opening up space in the centre of the pitch for the ball carrier to play a second line pass to Neymar. This also opened up the possibility for Di Maria to quickly spin and make a forward run to support Neymar after the pass was played, with Wijnaldum unlikely to react quickly enough to track the run due to the natural advantage the attacker has in these situations.

However, the issue for PSG lay with the development of play after Neymar had received the ball. Receiving the ball with your back to goal naturally invites immediate pressure from behind, and whilst that isn’t necessarily a problem for someone with the technical talent and ball retention ability of Neymar, the lack of support around the ball made it difficult for PSG to consolidate possession in this higher area of the pitch and force Liverpool back into a low block.

With Liverpool so compact centrally, they were able to block passes to Cavani and Rabiot, leaving Neymar with only wide options to pass the ball. The long switch to Mbappe was risky and difficult, whilst the lay-off to the overlapping Bernat usually led to the turnover of possession, with Liverpool usually able to shift over and press to exploit Bernat’s lack of 1v1 ability. The lack of options often forced Neymar to hold onto the ball and go on long dribbles into tight, crowded areas, and even for a player of his ability, the challenge of beating a group of three or four players within the space of a few metres proved too much.

Liverpool’s narrow shape also looked to set traps for Marquinhos, playing out of position in defensive midfield. In possession, Marquinhos would often drop between the centre backs to make a situational back three, allowing PSG to stretch Liverpool’s front three to try and create bigger gaps to play through. However, when he didn’t, and instead tried to receive behind Liverpool’s attackers, Klopp’s men were able to collapse on the ball aggressively from all sides and force a rushed pass or turnover.

Liverpool’s Stable Possession

Liverpool adopted a risk-averse approach to possession, using their central midfielders to pull wide to create overloads in deep areas, in a manner similar to the possession play of Zidane’s Real Madrid.

The numerical superiority in these areas primarily allowed Liverpool to control large periods of the game through stable U-shaped possession outside PSG’s block, putting their opponents in a situation which they are perhaps not used to, with their dominance in Ligue 1 naturally resulting in very few stretches of games where they do not have the ball. However, another key advantage of this structure was that Liverpool were able to protect against counter attacks from the ever-threatening front trio of PSG through strong coverage of the half spaces and the centre. This occupation of key spaces led to rather disjointed transition phases from PSG, with little space to run into and players too far apart for combinations to be made.

The way Liverpool structured themselves almost essentially split the team in half, with the five deep players responsible for control and protecting the team in transition, and the five more advanced players looking to create chances. The main route of attack for Liverpool was through wide areas, seeking to create 2v1 situations with the overlapping or supporting (from behind) full back, who of course had more license to advance forward given the protection offered behind them by the near central midfielder.

Wide Overloads and Ineffective Transitions

PSG generally did a good job of blocking the centre, with Rabiot and Di Maria blocking passing lanes into Salah and Mane, who operated as usual inside in the half spaces. However, PSG’s lack of access to press the ball – partially due to the aforementioned overload Liverpool had, but also due to the lack of defensive work rate from their own front three – meant that Liverpool’s deeper players could easily clip passes into the open full backs. PSG’s three-man midfield naturally could not cover the width of the pitch, leaving the wide areas unmanned, and although it is not exactly necessary for players like Neymar or Mbappe to track back – indeed, having your best attackers high up is very advantageous – they do need to contribute to the defensive effort from their higher position, either through blocking passing lanes to the full backs or by directing play into central areas through curved/angled pressing runs.

Once Liverpool were able to work the ball to their full backs, they looked to exploit the overload situation and create space for a cross. This was best exemplified by the first goal, where both full backs were somehow able to put in an uncontested cross in the same possession sequence, with support from Neymar or Mbappe nowhere to be seen.

Furthermore, PSG were not even able to utilise the advantages of having their front three remaining in high positions. There was too great a disconnect between midfield and attack to link play, whilst the distance between the front three themselves was also too large. As a result, it was difficult to make effective runs off the ball that could create space for the ball carrier, for the simple reason that the player making the run was too far away to affect defenders near the ball.

This led to PSG’s attackers ultimately becoming isolated and unable to hurt Liverpool with quick, direct counters. With the attackers not contributing enough defensively, and yet also unable to be effective in offensive transition, the play of PSG ultimately had a very disjointed feel to it, with players struggling to support their team mates in the different phases of the game.

Conclusion

The two late goals – one for each side – both came from situations where possession was regained as the other team tried to transition from defence to attack. There has been much talk about the benefits of these situations, which essentially gave rise to the popularity of counter-pressing in the modern game, and the two goals were a great example of how the opponent can be most disorganised and/or vulnerable when they have just won possession back.

PSG improved in the latter stages of the game after Tuchel switched to a 4-4-2 diamond, allowing Mbappe to be positioned closer to Neymar – it was these two that combined effectively to score PSG’s equaliser – but their goal was their only shot on target in the second half (out of just two shots altogether) and Liverpool’s late winner was probably deserved on the balance of play. The disjointed nature of PSG’s performance will worry Tuchel but it is still very much a work in progress.

Read all our tactical analyses here

- Liverpool 3-2 PSG: Liverpool edge deserved victory against dysfunctional PSG - September 21, 2018

- Tactical Analysis: France 1-0 Belgium | Set Piece Decides Game Dominated by Determined Defences - July 14, 2018

- Tactical Analysis: Manchester City 4-1 Tottenham Hotspur | Guardiola extends winning run to 16 - December 20, 2017