Perry Littman conducts a review of the existing scientific literature surrounding penalty kicks.

Penalty kicks in football appear to have been undervalued, as they are a golden moment to score in a game in which scoring is the most crucial part of football. Football is considered a low scoring game and a penalty kick can often be the difference between winning and losing and, therefore, should be seen as a highly valuable set-piece to football teams. In Men’s professional football, Penalty success rates vary between 70%-85%.

| Table 1. Conversion Rates in previous studies. | |||

| Author (Year) | Competition | Penalties | Conversion rates |

| Palacios-Huerta (2003) | Pro games England, Spain, Germany, Brazil, Argentina. | 1,417 | 80.10% |

| Jordet (2007) | WC, Euro, Copa America | 409 | 70% |

| Bar-Eli (2009) | EPL, SLL, GBL, ISA, FL | 311 | 75%-85% |

WC= World Cup, Euro= European Championship, EPL= English Premier League, SLL= Spain La Liga, GBL= Germany Bundesliga, ISA= Italy Serie A, FL= France League 1.

Some studies have highlighted the impact of anxiety and pressure that the kicker experiences when taking a penalty kick) and how this pressure affects their performance. For both the goalkeeper and penalty taker involved in a penalty kick, it can be one of the most pressured and intense moments in a competitive match. Typically, goalkeepers have between 300 and 800 milliseconds to react and save a penalty. Palacios-Huerta (2003) revealed that it only takes 0.3 for a penalty taker to score a goal from the penalty spot. Goalkeepers are required to position themselves on the goal line during a penalty kick, and due to the now-common use of VAR (Video assistance referring), this rule is being strictly enforced, making a goalkeeper’s job slightly more challenging. Goalkeepers usually tend to guess where the ball is going rather than relying on speed and agility to stop the ball (Palacios-Huerta, 2003; Bar-Eli, 2007). Goalkeepers feel the need to make an effort to dive and commit themselves either left or right. Attempting to stop the ball makes the goalkeeper feel more satisfied rather than staying in the middle and performing an inaction (Anderson, 2008; Bar-Eli, 2007).

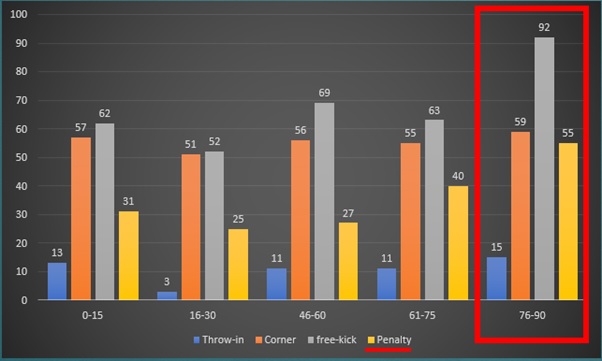

Cerrah (2016) investigated the effects of 1020 set-pieces scored in the Turkish Superlig over five seasons (2006-2007 to 2010-2011) based on realization time and the status of being the home or away team. In this study, the results indicated the highest number of set-piece goals were scored between the 76th and 90th minutes with added time, claiming a deterioration of physical conditions, attention, and concentration deficits affected this result.

Image 1: Distribution of set-piece goals based on goal type in Turkey’s Super League (2006-2007 to 2010-2011). (Cerrah, 2016)

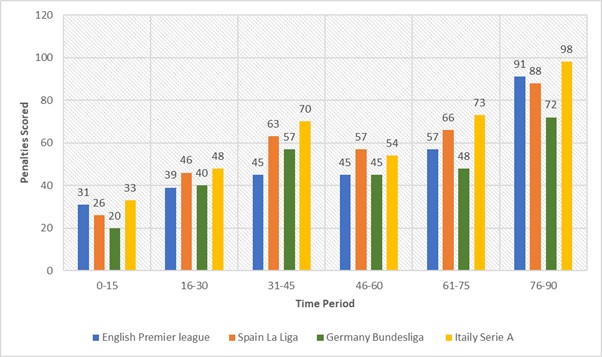

Image 2. Time period of the total of penalties scored in Europe’s top 4 leagues during the 15-16 to 18-19 seasons. Including added time penalties scored in the 31-45 and 76-90 period.

Image 2 highlights the increase of penalties scored in each league between the 76-90th minute, including added time. This figure also backs up Cerrah 2016 study mentioned earlier.

Also, being the home team has a significant advantage, according to Cerrah et al (2016), with a greater proportion of set-piece goals being scored at home. As with many team sports, Home teams are influenced by motivational influences of the crowd, venue familiarity (Dohem, 2008), and travel factors placed on away opposition (Dawson, 2019). Match officials have also been identified as a pivotal source to influence the home team though bias judgment. (Pollard, 2008). There is a positive relation between home advantage and points won in England, Spain, Germany, Italy, and France (Saavedra García et al., 2013).

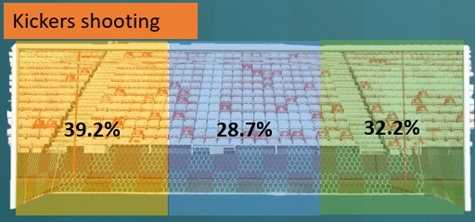

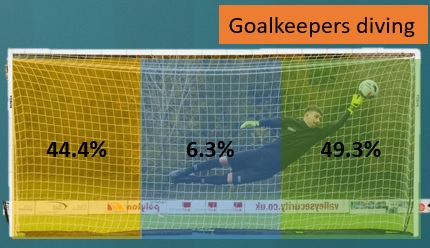

Bar-Eli (2007) analysed 286 penalty kicks, the results in this study showed that slightly more shots were placed to the kickers left side of the goal (39.2%) compared to the right (32.1%) or centre (28.7%). With most penalty takers being right-footed, this study suggests players will shoot across their bodies. Bar-Eli (2007) also recorded the jump directions by the goalkeeper, showing that the keeper would choose to dive to his left (opposite direction of the kicker’s attempt) on 49.3% of occasions compared to diving to their right side 44.4% of the time and remaining in a central position on 6.3% of occasions.

Image 3. Image of a goal showing the placement of shots from Bar-Eli’s (2007) study.

Image 4. Image of a goal showing the diving direction made by goalkeepers from Bar-Eli (2007) study.

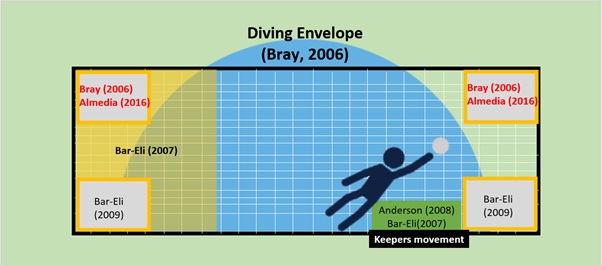

Ken Bray, the author of How to Score (2006), states that Kickers have an optimal placement to aim at the goal with goalkeepers only having a finite reach (a diving envelope, shown in figure 1) which is as about as far as the goalkeeper can reach (a limit to a fingertip save). Kickers should aim for the unsavable zone, which boasts a conversion rate of over 80%. The best location of the goal is by hitting the ball high and into the corner. It does risk the ball going over the bar, but aiming high does provide a struggle for keepers as their top hand is not usually enough to reach for the ball. Almeida, (2016) also concluded that the best strategy was to aim high into the corners. However, on the contrary, Bar-Eli et al, (2009) concluded that the best strategy was to strike the ball hard and low across the ground and as close to the goalpost as possible.

Different techniques of striking the ball have been previously investigated. In the 2006 world cup in Germany, 90% of the penalties taken showed players emphasizing placement over power. (Lees & Owens, 2011). Placement can be more comfortable to execute than power, and more secure as players are more fixated on the goal, specifically the edges. When striking the ball with power, the kicker is more fixated on the ball and tends to kick more centrally. Striking the ball low has also been believed to provide a better chance for scoring as they can provide much more power and making it challenging for goalkeepers to reach.

Previous studies appear to have ignored a chipped shot (commonly known as a Panenka), which is chipping the ball into the goal. The Panenka is a riskier method that makes the goalkeeper believe that the kicker is going to go for power and into the corner and forcing them to make a decision and commit to diving into either corner, this then allows the kicker to chip the ball into the middle. Czechoslovakia’s International footballer Antonin Panenka originated the chipped shot in his nation’s shoot-out victory over Germany in 1976 European championship final. When interviewed about the kick post-match, he said it was the ‘easiest’ and ‘simplest’ way of scoring a goal. Morden day football players such as Sergio Ramos, Zlatan Ibrahimović, and Lionel Messi still attempt this chipped spot-kick technique.

When studying the penalty technique of Cristiano Ronaldo, Palacios-Huerta (2018) stated that the pause in his run-up would result in an 85% chance that he would kick to the keepers right, which he states could have helped the Chelsea goalkeeper Petr Cech deny the Portuguese in the champions league final 2008 (Kuper & Szymanski, 2014). The stutter run-up kick provides pressure on the goalkeeper. It can be distracting and disrupt the keeper’s focus. Making the keeper think more and lose focus. (Kuper & Szymanski, 2014). Also, in terms of the slow run-up, the kicker can then observe the keeper more to see if he has committed himself already before the kick (Kuper & Szymanski, 2014).

Match Status has also been previously investigated, and most studies have discovered evidence to support the idea that the status of a match (whether teams are winning, losing, or drawing) influences the technical, tactical, and strategic behaviours of teams. Some studies have focused more specifically on corner kicks claiming they are taken most often during the draw status of matches as teams tend to be more actively trying to score in order to take the lead (Baranda & Lopez-Riquelme, 2012), although Casal et al., (2015) disagreed and states that draws are, in fact, the most common status in matches thereby explaining the more frequent corners during this state. Baranda and Lopez-Riquelme (2012) also revealed that teams in a winning position perform more short corners, short kicks, and outswing corners as opposed to teams that are losing or drawing.

Palacio-Huerta (2003) looked at time periods when penalties were scored. The second half has a slightly lower scoring rate for converting penalties (78.3%) than the first half (82.9%). This study also looked at Match status, and their results suggest that the scoring rate is slightly higher in tied matches (81.9%) compared to the rate when the kicker’s team is behind by a goal (80.2%), and the rate when the kicker’s team is ahead by a goal (77.8%).

Image 5. Image of a Goal with a combination of previous research results for optimal location to place the ball. Including Bray’s (2006) diving envelope and goalkeeper’s movement (Anderson, 2008; Bar-Eli, 2007).

From the research carried out on penalty kicks, we can see a variation and similarities in certain variables.

Read all our Opinion articles here.

Detailed references follow

Andersson, P., Ayton, P. and Schmidt, C., 2009. Myths And Facts About Football. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, p.105.

Almeida, C., Volossovitch, A. and Duarte, R., 2016. Penalty kick outcomes in UEFA club competitions (2010-2015): The roles of situational, individual and performance factors. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 16(2), pp.508-522.

Bar‐Eli, M. and Azar, O., 2009. Penalty kicks in soccer: an empirical analysis of shooting strategies and goalkeepers’ preferences. Soccer & Society, 10(2), pp.183-191.

Bar-Eli, M., Azar, O., Ritov, I., Keidar-Levin, Y. and Schein, G., 2007. Action bias among elite soccer goalkeepers: The case of penalty kicks. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28(5), pp.606-621.

Bray, K., 2008. How To Score. London: Granta, p.177.

Casal, C., Manerio, R., Arda, T. Losada, J and Rial, A. 2015. Analysis of corner kicks success in elite football. International journal of performance analysis in sport, 15, pp.430-451.

CERRAH, A., ÖZER, B. and BAYRAM, İ., 2016. Quantitative Analysis of Goals Scored from Set Pieces: Turkey Super League Application. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Sports Sciences, 8(2), pp.37-45.

Dawson, P., Massey, P. and Downward, P., 2019. Television match officials, referees, and home advantage: Evidence from the European Rugby Cup. Sport Management Review, 553, pp.1-3.

DOHMEN, T., 2008. THE INFLUENCE OF SOCIAL FORCES: EVIDENCE FROM THE BEHAVIOR OF FOOTBALL REFEREES. Economic Inquiry, 46(3), pp.411-424.

Jordet, G., Hartman, E., Visscher, C. and Lemmink, K., 2007. Kicks from the penalty mark in soccer: The roles of stress,skill, and fatigue for kick outcomes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(2), pp.121-129.

KUPER, S. and Szymanski, S. 2014. SOCCERNOMICS. New York: HARPERCOLLINS Publishers, p.142.

Lees, A. and Owens, L., 2011. Early visual cues associated with a directional place kick in soccer. Sports Biomechanics, 10(02), pp.125-134.

Saavedra García, M., Gutiérrez Aguilar, Ó., Marques, P., Torres Tobío, G. and Romero, J., 2013. Calculating Home Advantage in the First Decade of the 21th Century UEFA Soccer Leagues. Journal of Human Kinetics, 38, pp.141-150.

Palacios-Huerta, I., 2018. From Galileo to penalty shoot-outs: Data, economics and human behaviour. [online]. Available at: <https://lsedesignunit.com/News/Latest-news-from-LSE/2018/07-July-2018/from-galilieo-to-penalty-shootouts/index.html#group-ignacio-BHNYptxdz1>.

Palacios-Huerta., 2003. Professionals play minimax. The review of economic studies, 70(2), pp.394-415.

Pollard, R., 2008. Home advantage in football: A current review of an unsolved puzzle. The open Sports science journal, 1(1), pp.12-14.

- Penalty kicks: A literature review - June 19, 2020

- Analysis: Why have Southend United struggled in defence? - June 4, 2020

- Hipster Guide 2016-17 : West Ham United’s tactics, key players, and emerging talents - August 11, 2016