Vishal Patel takes a close look at Chelsea’s defence to understand why the club conceded so many goals in the 2019-20 Premier League.

Frank Lampard’s first season in charge of Chelsea was a broadly positive one. The club secured Champions League football, and made an appearance in the FA Cup final. A summer of spending has left Stamford Bridge feeling optimistic about future prospects, but a few issues continue to linger. Chief among them are Lampard’s inability to organise a defence. Chelsea ended up conceding 54 goals in the league, more than sides like Brighton, Burnley, and Crystal Palace. Having the 12th best defensive record in the league is certainly not the way to titles, and we’ll try and get into why Chelsea face these problems.

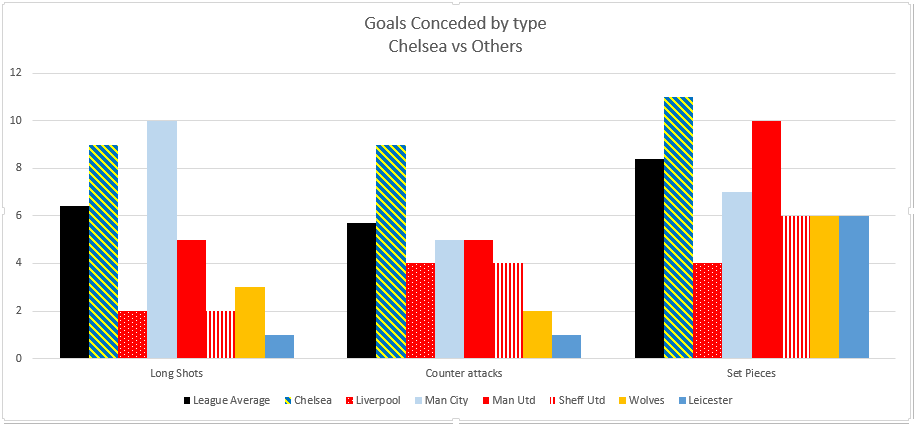

Of the 54 goals Chelsea conceded in the league last season, a quick look at the type of goals conceded points the way forward. The Blues conceded an inordinately high amount of goals from set pieces, long shots, and counter attacks (11, 9, and 9 respectively). These figures are well below the league averages (8.4 for set pieces, 6.4 from long shots, and 5.7 from counter attacks respectively). For the sake of this article, we will focus primarily on counter attacks, and try to isolate why Chelsea tend to struggle so much while defending them. The long shot goals stem partly from the same issues, and the keeper situation has been covered in depth. Set pieces have been another area of concern, and perhaps we will attempt to study this is a separate article.

Chelsea struggling to contain counter attack, long shot, and set piece goals, compared to their peers and the league average.

A quick glance at a few more defensive stats might help us understand the issues Chelsea are facing a little bit better. In terms of shots conceded, Chelsea actually did rather well, conceding only 7.13 shots per game, against a league average of 10.63. Only City keepers faced fewer shots per game than Chelsea, as the Blues outperformed even the mighty Liverpool on this metric. However, a closer look at the quality of shots conceded clarifies the picture a little more. The average shot Chelsea had to face was about 17.1 metres away from goal, or to put it slightly differently, the average shot Chelsea faced was from the edge of their own penalty area. Unsurprisingly, Chelsea are below average when compared to the league on that metric, with the average standing at 17.5 metres, and league winners Liverpool performing much better, and facing their average shot from 17.61 metres away.

Clearly, Liverpool’s defence have done a fine job of keeping their opponents far away from their goal, while Chelsea haven’t been quite as successful. This stacks up well with Jurgen Klopp’s identity as the high priest of pressing football. Klopp’s Liverpool, like his Dortmund, are adept at winning the ball back higher up the pitch. In fact, most successful teams across Europe utilise some form of pressing, and generally do so effectively for their results. It isn’t a coincidence that the last two winners of the Champions League are perhaps the two most aggressive pressing teams in all of Europe. So a few stats for Chelsea’s pressing could be useful to look at. The most widely accepted stat to measure pressing intensity, PPDA, is a good starting point. PPDA expanded is Passes Per Defensive Action. As the name suggests, the stat seeks to measure the number of passes a team allows the opposition to make before executing a defensive action (defensive duel, foul, interception, sliding tackle). Therefore, a lower number indicates a more intense press. In the Premier League, Southampton top the list in this regard, with a PPDA of just 8.16. Chelsea actually press more aggressively than most sides, which is reflected in a PPDA of 9.65 (vs a league average of 11.46), but are behind both Liverpool, who clock in a PPDA of 8.66. Indeed, it is also slightly behind the imperious Bayern Munich side, whose PPDA averages at 8.36. In theory, this should translate to a very high amount of ball recoveries in the opposition third of the pitch, as PPDA measures this for the higher 60% of the pitch. But this is where Chelsea’s pressing seems to fall short. Both Bayern and Liverpool make over 20% of their ball recoveries in the final third (20.2% for Bayern, 21% for Liverpool). The corresponding number for Chelsea lies at 17%, and immediately points out a flaw in the Chelsea press. So what’s going wrong?

Chelsea are pressing intensely (PPDA, lower is better), but not effectively (final 1/3rd recoveries, higher is better)

Most teams aspiring to be near the top of the football pyramid, and those at the top of it tend to play a style that incorporates pressing high up the pitch. The difference between those that succeed and those that don’t tends to lie in the efficacy of their pressing. So while Chelsea can always shift to playing a different way, Lampard’s tactical philosophy seems to dictate that they will look to press the opposition close their goal. Given the numbers above, it does appear that Chelsea are very willing to press and make the effort, but the fact is that they don’t do so very effectively. Clearly, teams are able to play beyond the Chelsea press, and attack their back line. So what are teams like Liverpool and Bayern doing? Well, firstly, they simply aren’t losing the ball that much. More importantly, they don’t lose it in the wrong areas of the pitch. Liverpool tend to lose the ball mostly in the opposition’s third, with about 56% of their losses happening there. This is the best in the league, along with City. On the other hand, only 46% of Chelsea’s ball losses are in the opposition third. While that figure in itself doesn’t look disastrous, it’s just slightly above the average, and lower than the corresponding figure for sides like Sheffield United, and even Watford. That might hint as some issues with the structure Chelsea hold in their build up, causing ball losses in the wrong areas of the pitch. But the most important issue what Chelsea dont do in the moments just after losing the ball, and what teams like Bayern and Liverpool do in these situations.

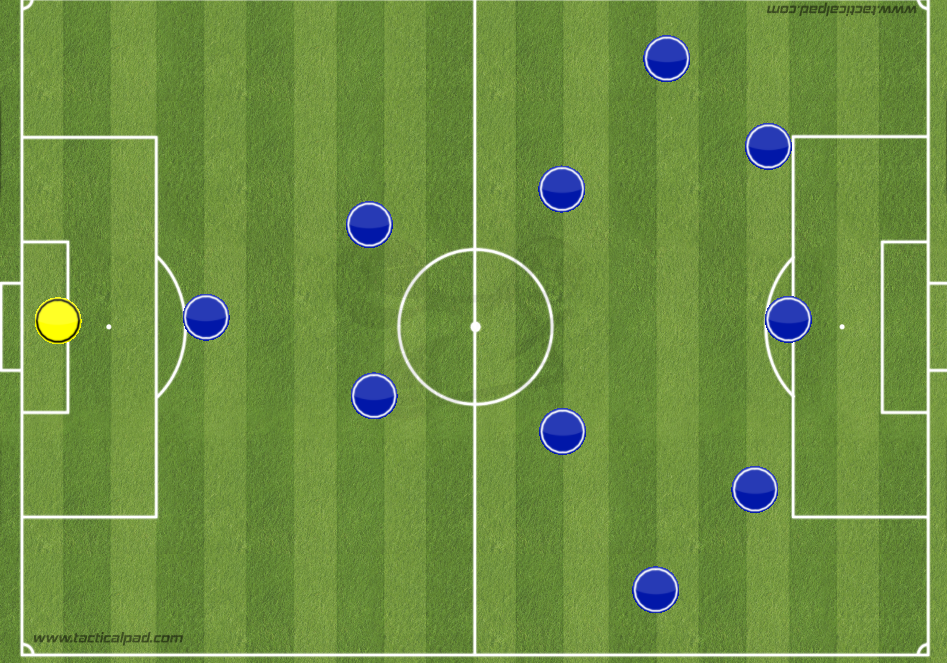

Typically, the top teams tend to attack with both full backs, and leave 2 to 3 players in deeper areas to guard against the counter. The arrangement and functions of these players tends to make the difference during the counter-press that ensures a team regains the ball higher up the pitch successfully. Typically, sides like Liverpool and Bayern push these players up further to close the space between the lines. In most scenarios, these sides man mark any attackers that the opposition have left up for the counter, and play a sweeper in behind.

Liverpool’s shape on the ball

The idea of using this shape is to create and maintain access to the opponent’s ball players when they have the ball. Constant access to the opposition’s counter-attackers serves to slow the counter down in its infancy, often forcing play backwards, and into a wall of pressure from retreating attackers.

Here you see Liverpool creating access to the attackers as Wolves try to build their attack.

Here we see TAA closing down the receiver, with Fabinho and van Dijk marking attackers closely. Simultaneously, Joe Gomez is dropping deeper to sweep up any balls that come in behind.

From the same match, Fabinho is closing down the receiver, therefore slowing down the counter attack.

On the other hand, Chelsea simply haven’t been able to stop counter attacks because the defensive line/players simply dont push up to challenge for the ball once it is lost. The defenders tend to drop deep to protect the space in behind, but this inadvertently leaves too much space in midfield to exploit.

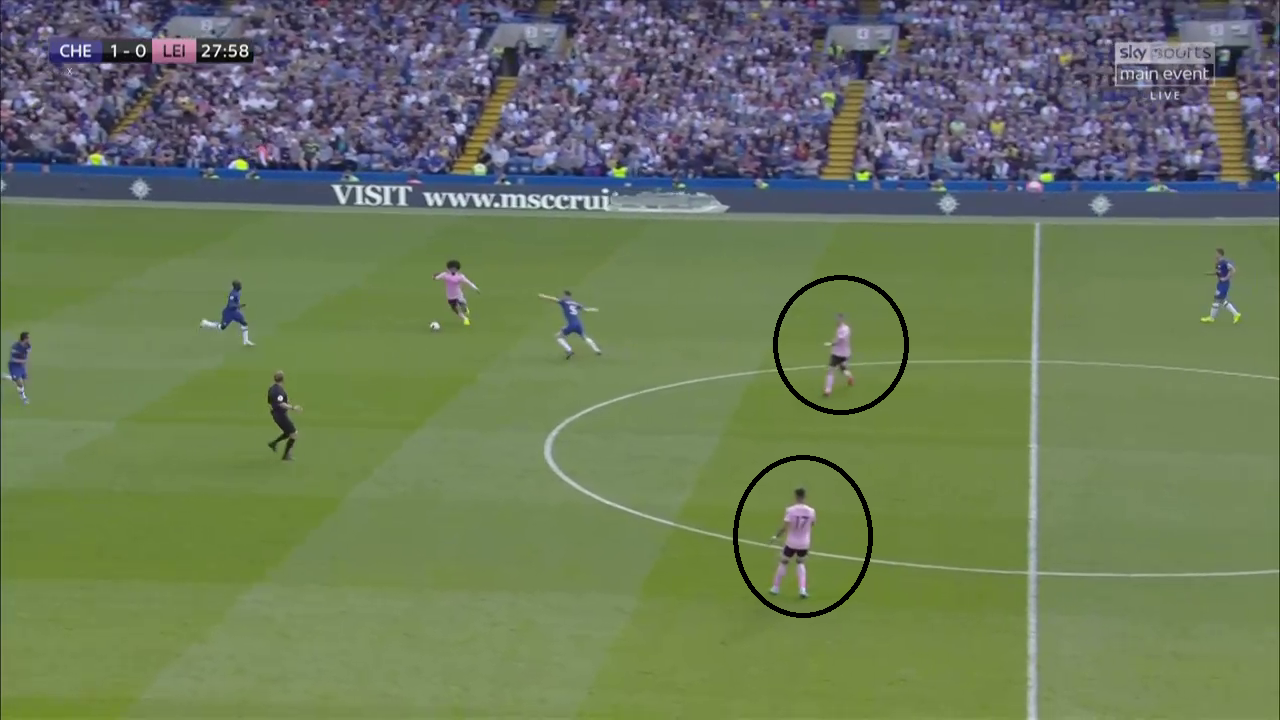

Chelsea defenders drop very deep upon losing the ball, therefore there is a massive amount of space to exploit between the midfield and defence. Teams on the break can exploit this fairly easily once they get past the first line of pressure.

Jorginho is no position to pressure the ball here (given his distance from Choudhury), but Perez and Maddison are in space behind him, as the Chelsea defenders have dropped deep.

Another image from the same match against Leicester – Chelsea lose the ball after an attack, and Maddison is free to pick up the ball under no pressure whatsoever, because the Chelsea defence is in retreat.

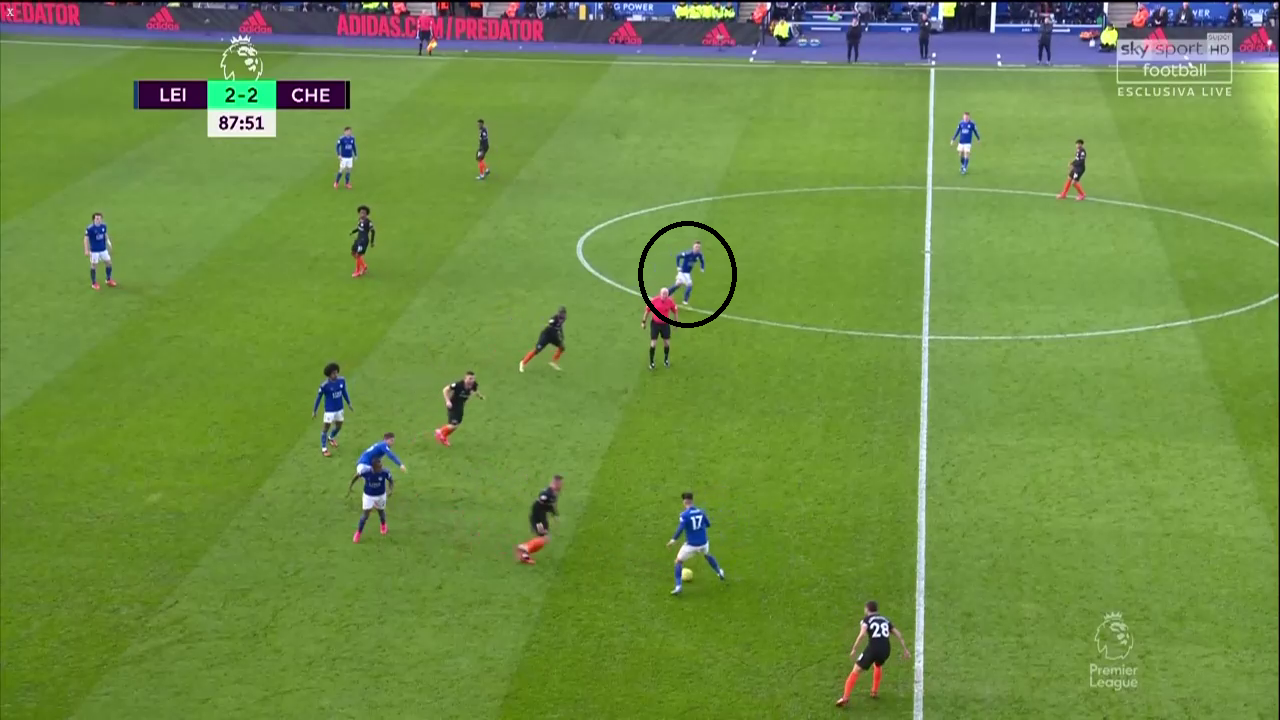

In the return leg against Leicester, Chelsea have just lost the ball here in midfield. Azpilicueta is too far away from Perez (who was behind the Chelsea midfield) to put any meaningful pressure on him. More importantly, Maddison (highlighted) is also running in behind Kante, and has a free run at the centre backs (who are too deep to challenge him immediately).

As if to exacerbate the point, Chelsea’s recent PL game against Liverpool saw this image. Chelsea have just lost the ball after an attack. Henderson is able to receive the ball in space, with the Chelsea midfield absent. A few seconds later Henderson’s long ball puts Christensen in an awkward position, and the defender is sent off.

From the same match, Liverpool have just lost the ball here. Zouma is forced to play it long as his nearest options are all marked, with the outball Werner (bottom left corner) also being marked by Fabinho (just outside the image)

Conclusion

The lack of a solid counter-pressing structure is clearly impeding Chelsea’s path to the next level. Of course, a team doesn’t necessarily have to play with a high pressing and counter-pressing approach, Chelsea seem to have chosen that path consciously. The Chelsea defence does look far more secure when they play three at the back because the team sits a lot deeper, playing with a block, and perhaps this is an option Lampard could turn to more often. However, given that Chelsea look set to play with four defenders and three midfielders, it does appear as though Lampard will need to find a solution to the pressing issues currently plaguing Chelsea.

Read all our Tactical Analyses here.

- Analysis: Are Chelsea’s pressing issues a concern? - October 5, 2020

- Has Financial Fair Play Been Worth It? - August 27, 2020

- Tactical Philosophy: Frank Lampard - May 20, 2020