Miles Olusina writes a detailed tactical analysis about the Copa del Rey final that finished Barcelona 3-1 Alaves

It was very much David vs Goliath in the 2017 edition of the Copa del Rey final, as La Liga giants Barcelona met newly promoted Deportivo Alaves, who had far exceeded all expectations this season. Having watched arch rivals Real Madrid claim the La Liga title on the final day, Barca were desperate to get their hands on their third successive Copa del Rey title in manager Luis Enrique’s final game in charge of the side.

As expected, Luis Enrique’s side entered the game as overwhelming favourites, given the huge gap in individual quality and the 6-0 thumping Barca handed the underdogs in February. However, Alaves were not a side to be counted out, surprising everyone by finishing in 9th place under the stewardship of manager Mauricio Pellegrino.

The match was a great one to watch with Barcelona very much on the front foot for the entirety of the game. However they found it very difficult to break down the Alaves defence partly due to their own poor positional structure in the early stages and the stellar organization of Alaves in their 5-4-1 shape.

It looked even for much of the first half until a moment of brilliance from Messi broke the deadlock on 29th minute. A wonderful free kick from full back Theo Hernandez levelled the scoring, stunning the Vicente Calderon. Eventually though, Barca’s quality began to show and 2 goals late in the first half from Neymar and Paco Alcacer brought home the King’s Cup once again for the Blaugrana.

Line ups

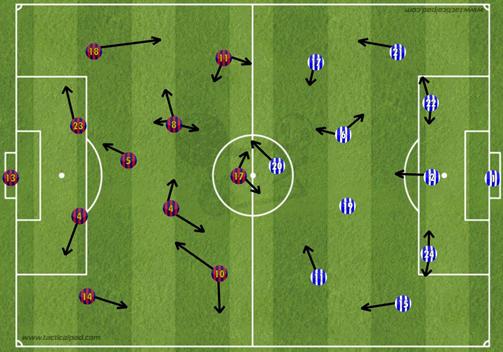

Barcelona (4-3-3): 13. Ter Stegen // 14. Mascherano, 4. Pique, 23. Umtiti, 18. Alba // 5. Busquets, 4. Rakitic, 8. Iniesta // 10. Messi, 17. Alcacer, 11. Neymar

Alaves: 1. Pacheco // 21. Femenia, 22, Vigaray, 2. Ely, 24. Feddal, 15. Hernandez // 17. Mendez, 6. Llorente, 19. Garcia, 11. Ibai Gomez // 20. Deyverson

Substitutions: 10’ Gomes (Mascherano), 82’ Vidal (Rakitic) // 58’ Camarasa (Mendez), 59’ Ibai Gomez (Sobrino), 78’ Romero (Hernandez)

Goals: 29’ Messi, 45’ Neymar, 45+3’ Alcacer // 32’ Hernandez

Alaves’ compact 5-4-1 shape frustrates Barca

From the offset, Alaves opted for the more passive approach against this Barca side, knowing that conceding too much space in behind would allow for vertical runs from the likes of Paco Alcacer and Neymar. They also knew that it was vital they did not concede in the early stages as from there it would have been an uphill battle.

To avoid conceding, they chose not to press Barca’s first line in the build-up phase, well aware of the ability of some of Barca’s more intelligent players to find space between the lines and play through pressure. Instead of pressing the first line and allowing Busquets to receive the ball behind their lines of pressure, they chose to remain compact vertically and pressed sporadically based on the position of the ball and whether they had sufficient access to the ball carrier.

It proved effective for much of the 1st half as Barca found space in the final third hard to come by. They were intelligent in that they blocked off passing lanes to key players in Barca’s circulation like Iniesta and Busquets through the use of cover shadows.

One of the keys to their inhibition of Barca’s attacking threat was the shifting of the defensive block when the ball reached the wide areas. Early in the 1st half, Barca seemed intent on playing through Neymar and relying on combinations between him, Jordi Alba, and Iniesta. With the Alaves block shifting quickly and efficiently however, Enrique’s side found it difficult to combine down that left side as the half-space was occupied by Mendez on the right of Alaves’ midfield.

It also allowed them to reduce Barca’s ability to create wide overloads as the midfield were able to provide cover for the wide player who moved towards the wing to press Neymar or Alba. The deployment of the back 5 was key also, as they could play what is known as a pendulating back 4.

Above we see the pendulating back 4 being deployed. It involves the full back nearest to the ball applying pressure to the ball carrier out wide while the remaining 4 defenders form a back 4 as cover in behind. The benefits of this are clear; it allows the full back to press the ball carrier but still provides adequate cover should he be beaten in a 1v1.

One issue they faced however, which ultimately led to Barca’s opening goal was their lack of man orientations particularly in the final third. This made them more susceptible to blind side vertical runs as their primary defensive reference point was the ball, as well as the overall team shape.

The image above highlights an example of where they were vulnerable to runs in behind. Messi receives the ball in the centre and plays a penetrative ball into Alba on the far side, as we see him do so often from that central position. In this instance, it is only made possible as a result of the Alaves defensive orientations. As is made clear by the field of view of the defenders, all 5 of them are fixated firmly on the ball; while of course aiming to remain as compact and organized as possible as a defensive unit and force Barca to play around their defensive block.

However, this has made them incapable of detecting the run of Alaba in behind their defensive line. This is partly due to Neymar’s half space positioning, which forces Femenia at RB to tuck in, freeing up Alba to make a vertical run unopposed. The lack of man orientation would have been acceptable had they chosen to apply more pressure on the ball. However, they chose to remain passive, allowing Messi the time and space necessary to pick out Alba.

Messi influential as Barca ball circulation improves

As good as Alaves were in terms of maintaining organization and occupying key zones on the field, Barca were equally bad in the early stages in their ability to maintain possession and move their opponents with their possession game. This was due primarily to Barca’s slow tempo in the early stages caused by poor and lethargic movements from supporting teammates who did not help the ball carrier.

Particularly when the ball was out wide, they struggled to retain possession as the shifting of the opposition block caused them to be underloaded in the wide areas. In the early stages, they emphasized chance creation down the left hand side; possibly because their strongest full back in an attacking sense in Jordi Alba was down that side, which could have potentially opened up the half-spaces for Iniesta and Neymar and allowed for combination opportunities between the three.

However, this proved futile as aggressive pressure from the Alaves midfield when the ball reached the wide area saw Barca concede possession rather frequently. There was nothing of note to worry about in their defensive transition though, as Alaves were reluctant to push too many players forward in order to avoid falling victim to a counter themselves.

As Messi’s influence grew, Barca began to use the ball much more effectively as the midfield line in particular became more concerned with his movements into the centre. Here he is above, rotating with Rakitic as they aim to force individual players to vacate their position within the block to create space in midfield for their teammates.

And it was movement such as this from Messi that led to the opening goal in the 29th minute. He begins on the right, as he so often does, which makes his central movements more inconspicuous and has the potential to drag the full back away from the wide area and create space for the Barca right back. Unfortunately, Mascherano and later Gomes at right-back were not particularly skilled in attacking from wide zones.

It is his qualitative superiority and ability to draw players in that makes him so effective, as is evident with his goal. The idea of qualitative superiority is that 1v1 situations always favour the more skillful player. However, with someone such as Messi who is so supremely gifted on the ball, the opposition need to put 2/3 players on him to ensure he is unable to have an effect on the game.

In response to Messi receiving the ball in the centre, the 2 Alaves midfielders react instantly to apply pressure on him. Ely, in the middle of the Alaves defence, leaves the defensive line to provide additional cover between the lines, should Messi evade the 2 midfield players.

Paco Alcacer then threatens to make a run in behind the defence which means the right centre back and right back must move centrally to maintain compactness in the defensive line. As their primary focus is the ball carrier, in this instance Messi, and their defensive shape, they do not pick up Neymar who is able to receive possession and combine with Messi to give Barcelona the lead.

The depth provided by Paco Alcacer up front also proved instrumental in Barca breaking the lines of the Alaves defensive block. He very rarely contributed to chance creation; instead looking to find space in the 18 yard box and force back Alaves’ defensive line. As Alaves aimed to push forward to press Barcelona, they were unable to do so with as much compactness as they were reluctant to allow Alcacer to be found in behind their defence. This led to a disjointed pressing structure, facilitating Barca’s ability to find space between the lines.

Conclusion

A consolation for los Cules after what has been quite a mediocre season by their standards. An adequate performance was enough to hand them their 9th trophy under Luis Enrique’s tenure; however this does little to gloss over the glaring problems within the Barcelona set up. With all but one of their summer signings in Samuel Umtiti underperforming, heavy defeats away from home to Juventus and PSG in the Champions League and key players such as Iniesta and Mascherano beginning to age, Barca will hope that some much needed changes are implemented under incoming manager Ernesto Valverde.

Read all our tactical analyses here

- Scout Report: Marcus Thuram | Gladbach’s attacking sensation - July 17, 2020

- Tactical Philosophy: Paulo Fonseca - May 28, 2020

- Maurizio Sarri at Chelsea: Tactical Approach & Key Players - September 5, 2018